Introduction

Increasing in size and diversity, Melbourne’s film festival scene is a growingly essential segment of Melbourne’s cultural offerings. But more than that, audience focused film festival ecosystems – like Melbourne’s – are increasingly essential to the overall sustainability of the non-blockbuster film sector. In this article I seek to contribute to the field of film festival studies through an interrogation of Melbourne’s film festival network as it was composed between the 1st of March 2020, and the 1st of March 2021. I achieve this through the use of Social Network Analysis (SNA), a method that focuses on analysing the connections within a system instead of the nature of individual actors. Both festivals and independent exhibitors are considered as part of this system, and their interactions on social media website Twitter are recorded as the analysable data. The result of this research is a mixed-methods, descriptive discussion of Melbourne’s film festival network as it was composed in the timeframe.

The aim of this project is to begin to address two central research questions:

- What is the shape and structure of Melbourne’s film festival network?

- Who are the key actors within Melbourne’s film festival network?

As is the case with any descriptive study that incorporates qualitative data, this research non-generalisable, and perhaps raises more questions than it provides answers. However, this article’s process and aim is notable insofar as it directly addresses a significant gap in existent literature – analysis of how festivals and exhibitors relate and operate within the film festival network. Ultimately, I engage with this topic in the hope that it will inform future research and perhaps the management of existent and future festivals.

Literature Review

Film festival scholarship has largely focused on two kinds of festivals: business or prestige festivals, and audience festivals (Carroll Harris, 2017; Richards & Carroll Harris, 2020). ‘Business festivals’ are film festivals which largely exist to benefit those within the industry (Carroll Harris, 2017). They are internationally significant events which facilitate industry networking, the marketing films for distribution, and are propellants of celebrity (Carroll Harris, 2017; Richards & Carroll Harris, 2020; Wong, 2011). These festivals are typified by prestigious international film festivals such as the Cannes Film Festival and the Venice Film Festival (Stevens, 2016b). Stevens (2016b) notes that this kind of film festival had its genesis in a post-World War Two Europe which sought to re-affirm national identity and cultural significance after the war’s devastation. This is where the notion ‘prestige’ intersects with this kind of festival. These festivals operated – and continue to operate – as bombastic celebrations of their host cities, facilitating the growth of the cultural capital of these spaces (Wong, 2011). And this connection between festival and cultural significance pertains to the filmmakers of these festivals as well. These festivals are often where creatives are culturally canonised and artistically legitimised in the consciousness of the international film industry (Wong, 2011). As de Valck notes, these festivals act as the ‘Olympics of film’ (quoted in Stevens, 2016b, p. 30): spaces of competition and pageantry that act as sites for the negotiation of power and identity within the industry and amongst the culturally elite (Wong, 2011).

However, Australian film festivals exist in a very different framework, and are more ‘audience-oriented affairs’ (Stevens, 2016a, p. 3). As opposed to the post-war emergence of business festivals in prestigious cities of cultural capitol, Australia’s first known film festival occurred in a small tourist town, Olinda, in 1952 (Stevens, 2016b). From grassroots origins, Australian festivals have emerged in service of their audiences (Stevens, 2016b). Australian festivals are largely ‘audience festivals’: festivals where the intended beneficiaries are cinephile audiences instead of industry elite (Richards & Carroll Harris, 2020). Operating with little pomp and celebrity, and often smaller in size, Australian festivals regularly cater to specific niche interests or non-hegemonic identity groups (Stevens, 2016b; Wong 2011). This approach is typified by an observation made by the 1976 organisers of the Melbourne Film Festival: ‘A film festival is two things: film and people’ (quoted in Stevens, 2016a, p. 201). It should be noted that there is not a strict delineation between business and audience festivals (Richards & Carroll Harris, 2020). For example: the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) is an audience festival, yet it provides industry events such as a film marketplace (MIFF, 2021). For the most part, the Melbourne festivals in this study will be understood as audience festivals.

Thanks to this audience-oriented approach, film festivals have become an essential component of film distribution in Melbourne (Stevens, 2016a). These festivals can be the home for films that – due to their niche or narrow appeal – would otherwise be unviable to regularly distribute (Peranson, 2008; Stevens, 2011). Carroll Harris (2017) argues that, in such a way, the film festival market has largely replaced arthouse film distribution. This, they note, is due to the ‘blockbusterisation’ of the mainstream film market, where cycles of mega-budget films have pushed mid-to-low budget films to the periphery and out of traditional distribution (Carroll Harris, 2017, p. 47). Furthermore, Carroll Harris (2017) notes that there is no strong correlation between a film’s success at a festival, and its post-festival achievement. As such, festivals often represent the entire in-person audience for the films they exhibit (Carroll Harris, 2017). In this way, Melbourne’s festivals are self-enclosed distribution platforms that are an essential means of domestic distribution of films in Melbourne (Carroll Harris, 2017). As Richards (2016) contends while discussing the role of the Melbourne Queer Film Festival (MQFF) in the distribution of queer films in Melbourne; festivals are rarely a springboard to wider domestic distribution. Rather, they are the distribution itself.

Because film festivals have become an essential means of distribution for many films, they also play a role in the conditions for film funding. Rhyne (2006, p. 618) argues that, with regards to queer filmmaking, film festivals do not simply offer a means of exhibition for the films, but “create the economic conditions that enable their production”. The existence of a film festival circuit means that a film can be critically and financially successful without entering wider cinematic distribution; a phenomenon that Carroll Harris (2017) notes took place with the Australian film The Babadook (Kent, 2014). It appears much Australian cinema could similarly rely on festival distribution to be successful. The Australian film industry is a small, mid-to-low budget and heavily subsidised ‘cottage industry’ which, according to Verhoeven (2007), is positioned adjacent to European art cinema in terms of audience and reception (Gibbons, 2007; Maher et al., 2016). While more research would be needed to make a confident assertion, it would not be surprising that since similarly budgeted and received films rely on festival distribution, Australian national cinema may in part too. As such, developing a more comprehensive understanding of Melbourne’s film festival network potentially progresses the overall understanding of the lifecycle of Australian cinema, and a form of distribution that the industry may be reliant upon.

While most festivals in Melbourne have evolved from the diasporas and communities for which they cater, some exist to capitalise on the growing importance of festivals as a means of distribution. Richards and Carroll Harris (2020) recently termed this third kind of festival as the distributor-driven festival. ‘Distributor-driven’ festivals do not emerge from diasporas or marginalised identity groups, but instead cater to them (Richards & Carroll Harris, 2020). In Australia, the primary proponent of this form of festival is distributor Palace Films. Palace Films curates festivals and exhibits them exclusively at cinemas owned by their connected exhibitor, Palace Cinemas. Thusly, for Palace Films these festivals exist as a distribution opportunity. These festivals allow Palace Films to exploit films throughout their cinema locations that would otherwise be unviable as weekly releases (Richards & Carroll Harris, 2020). In a sense, this style of festival aligns most closely with audience festivals. However, they differ with regards to who is running the festival – a non-profit organisation vs. a distributor – and why the festival exists – to exhibit films for an audience vs. to exploit otherwise unviable films for renumeration. Furthermore, these festivals extend Palace Cinema’s brand identity – that of a boutique cinema chain for cinephile audiences – and have established a film festival franchise of sorts (Stevens, 2016b). Expanding on this much further is not necessary. However, it should be noted that several of the festivals in this study are a component of Palace’s distributor-driven film festival schema, and they play a significant role in Melbourne’s film festival ecosystem.

Palace Cinema’s influence in Melbourne’s film festival market speaks to why independent exhibitors have been included in this study. Carroll Harris (2014) notes that Australia has an oligopolistic exhibition industry, dominated by three cinema chains – Hoyts, Village, and Events Cinema. The programs of these massive chains are dictated by agreements with international distributors (Carroll Harris, 2014). Due to these agreements, programs are booked up to a year in advance, and generally homogenously spread amongst the cinemas (Carroll Harris, 2014). This leaves little-to-no chance for smaller productions not connected to massive distributors to screen at these large cinema chains; Aveyard describing these kinds of exhibitors as ‘like a film supermarket’ (2009, p. 196; Carroll Harris, 2014).

For the purposes of this article, independent exhibitors include all film exhibitors besides those owned by the major chains. Traditionally, these exhibitors have diversified from the major multiplex cinema culture by offering boutique alternatives that have an increased freedom to explore more niche offerings (Aveyard, 2009). However, thanks to the blockbusterisation of cinema distribution, this freedom has been greatly diminished. The exhibition of film festivals offers independent exhibitors the opportunity to diversify their programs without the risk of agreeing to the extended run of a film. On top of this, the ‘event’ like nature of a festival screening offers independent exhibitors the chance to attract audiences outside of their usual demographics (Stevens, 2011, 2016a). In this way, there is a reciprocity in the relationship between film festivals and exhibiting cinemas in Melbourne: as festivals rely on independent exhibitors to exhibit their films, and exhibitors can utilise film festivals to diversify their programming.

It is also important to note that while the number of festivals in Melbourne has been increasing, there is little to suggest that festivals have become competitive with one-another. In recent years, Melbourne’s film festival scene has exploded – increasing from 30 festivals in 2010 to 40 festivals in 2016 (Stevens, 2011, 2016c). However, Stevens (2011) argues that while this may suggest that Melbourne festivals are approaching market saturation, besides exhibiting films there is little overlap from festival to festival with regards to content. That is because each festival is specialised and caters to a specific audience (Stevens, 2016a). As such, there is little competition over resources and audiences as there is little similarity in programming from festival to festival (Stevens, 2011). Yet, there has not been much direct academic discussion of competition between independent exhibitors in this market. As addressed, film festivals and their event-like quality can be a means to attract audiences outside of an exhibitor’s regular demographic. As such, while this has not been directly theorised, there could be understandable competition between exhibitors with regards to attaining successful festivals for exhibition. Even so, as has been theorised so far, there is little direct indication of market competition within Melbourne’s film festival network.

Scholarly interrogations of Australia’s film festival environment have predominantly considered their nature, history, practices, and development. However, there is a gap in existent literature with regards to the public relationships between festivals and independent exhibitors, and ascertaining the structure of the Melbourne’s film festival network. Addressing this gap is the reason why I have decided to incorporate SNA into this space. SNA is a method that involves the identification of relevant agents (or ‘nodes’) in a social network, and then mapping the ‘extent of links between them’ (Veal et al., 2014, p.123). SNA focuses not on the individual value of nodes in a system, but on the relationship between nodes and the overall structure of the system (Zhu et al., 2010). SNA allows researchers to descriptively analyse the interconnections within a system to make comment upon the nature or structure of a network and its significant actors (Knoke & Yang, 2008).

This kind of analysis is existent, but not common in arts and arts management research (Veal et al., 2014). As a method of analysis, SNA has expanded in use throughout social sciences since its official inception in the 1960’s (Scott, 2012). There have been some uses of SNA in the broader field of arts and events management. One such example is Bendle and Patterson’s study of the interconnectivity of Australia’s grassroots creative arts institutions (2008). SNA has also been utilised in film production and distribution studies. Senekal has incorporated SNA into an interrogation of the artistic influence of South African filmmaker Pierre de Wet (2014). Furthermore, Hoyler and Watson used SNA to dissect the emergence of formal transnational film co-production agreements – such as those held between Australia, Canada, and the U.K. (2019). Most recently, Verhoeven et al. applied SNA to the production teams of the Australian, German, and Swedish film industries to interrogate gendered barriers and gatekeeping within the industries (2020). While SNA has been incorporated into adjacent fields, there is a specific gap with regards to the method’s application to Melbourne’s film festival network, as well as more broadly in the field of film festival studies.

None of the aforementioned SNA studies engaged in what Grandjean terms ‘digital humanities’: the growing pool of analysis of Web 2.0 spaces and interactions (2016). This article will also be addressing this gap by using Twitter as a site of study. ‘Web 2.0’ is a term initially used by O’Reilly to acknowledge what they saw as a major shift in the use of online spaces (Benson, 2016; O’Reilly, 2005). Web 2.0 describes the shift to a ‘participatory web’, where platforms began to be defined and reliant upon user generated content, interaction, and direct participation (Davies & Merchant, 2009; Ricke, 2014).

Many studies have interrogated the role of Twitter and other social media platforms play in the management of arts and cultural organisations. These studies have variously found that non-profit arts organisations are more active online than for profit organisations (Hausmann & Poellmann, 2013). Furthermore, various studies have found that arts organisations are often reliant upon social media platforms for engagement and revenue raising, particularly in the U.S. (Foreman-Wernet, 2017; Preece & Wiggins Johnson, 2011; Slatten et al., 2016). This is likely due to the low-resource requirement of social media outreach as compared to traditional marketing. This modern social media requirement is something that this article capitalises upon, as it enables the development of an insight into the structure of Melbourne’s film festival network.

Methods

As a general overview, this article provides a mixed-methods and descriptive SNA of the Twitter interactions that constitute Melbourne’s film festival network on Twitter. This mixed-methods format is being utilised to best address the aim of the research: to identify the structure of and most significant actors in Melbourne’s film festival system. As noted in the introduction, the scope of this project was tweets (blog posts made on Twitter) made by the accounts of film festivals or independent exhibitors between March 1st 2020, and March 1st 2021. To be included in the study, festivals and exhibitors had to hold a Twitter account, and have been – in some way – active during the timeframe. This eventuated in the Twitter accounts of 8 independent exhibitors and 33 film festivals being included in the study – leading to a studied network of 41 accounts. The interactions between accounts were rated on a zero-to-two scale: zero being no interaction between accounts; one being a mention or retweet of another account; and two being a direct endorsement of or dialogue with another account. This data was then visualised and quantitatively analysed with open-source graphing software, Constellation (Constellation, n.d.).

It should be noted that this timeframe lends itself to some unique considerations. This timeframe was chosen because of recency. However, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be an oversight to pretend this timeframe was ‘normal’. Due to the significant 2020 Melbourne lockdowns, many festivals had to cancel their offerings for the year. The few that did operate often had to post-pone proceedings – either for the year or for a short time – or shift to an online delivery of the festival. This obviously affected exhibitors too, as all those studied had to – at some point – shut down for a substantial portion of 2020. This, however, does not mean data-collection during this timeframe is fraught. As previously noted, all organisations studied were active, and all exhibitors resumed service once restrictions were lifted. While this may not be a ‘normal’ year, it perhaps offers a unique insight into who the most significant and stable actors in this network are. Also, there is significance in creating a ‘snapshot’ of this network in what was a critical year in the timeline of these organisations. As such, while COVID-19 no doubt impacted the results, the results themselves are still prescient.

It was decided that public data from social media would be used instead of other non-digital forms – such as interviews or questionnaires for the festivals and exhibitors to complete. A much more comprehensive dataset could be accrued by utilising already public information in the timeframe of this article’s writing. Twitter was chosen over other platforms due to the ease and thoroughness with which data could be accessed and assessed. As noted by Corbett and Edwards (2018): “although many social media corpora are available, the data scale and accessibility is not comparable to Twitter data”. The structure of Twitter is suited to research, as accounts are easily accessible, and the totality of an accounts public interactions are present on their homepage (Grandjean, 2016; Ovadia, 2009). For this project, I manually scoured each account to assure that no connections between accounts were missed. Additionally, Twitter’s processes of public engagement – tweets, retweets, and replies – incentivise making direct contact with other accounts (Black et al., 2012). As mapping the links between organisations is a central component of this project, Twitter suited the research’s needs.

This is not to say that Twitter as a site of study is perfect. In many countries, Twitter’s use is not significant enough to enable researchers to use it for study – such as in Germany (Suzić et al., 2016). This was not an issue in this case. However, as will be shortly noted, there were still some organisations that hold social media presences exclusively on platforms that are not Twitter, and as such were not included. Furthermore, with any social media research, there are important ethics considerations. While data is publicly available, its use should still be conducted carefully (Corbett & Edwards, 2018). This study could be considered a safe use of Twitter data, as only the public information of organisations, not individuals, was studied.

Of the 41 accounts studied, 8 were independent exhibitors. As noted in the literature review, ‘independent exhibitor’ was understood in this study as any exhibitor outside of the oligopoly that dominates Australian film exhibition. These accounts were drawn from the Independent Cinema Australia’s (ICA) list of metropolitan Melbourne member cinemas (ICA, n.d.). Of this list, 6 cinemas did not have a Twitter presence for the duration of the study, and thus were excluded. Furthermore, 5 of the cinemas in the ICA’s list were all owned and operated by Palace Cinemas, which utilises one Twitter account for all their locations. As such, the Palace Cinemas Twitter account was included in lieu of individual accounts for locations such as Palace Westgarth. Additionally, the ICA’s list did not include the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) – a Melbourne moving-image museum and specialty cinema. I decided to include ACMI as an exhibitor in the study, due to its importance as an exhibitor and facilitator of many of Melbourne’s festivals – such as the Birrarangga Film Festival.

Of the 41 accounts studied, 33 were film festivals. The list of film festivals for study was accrued through a combination of individual research and the listings of Australian film festival news website, Festevez (Festevez, n.d.). As with the exhibitors, several prominent film festivals were unable to be included due to period inactivity or not having a Twitter account altogether. A notable example that was excluded from the study for this reason was the St Kilda Film Festival – an esteemed short-film festival. It should also be noted that I included several film festivals that are not exclusive to Melbourne, but instead tour multiple cities. These are primarily the Palace Films festivals – such as the Italian Film Festival – which align with Palace’s distributor-driven model of festival delivery. The accounts of these festivals have been included as they are still significant to the structure Melbourne’s film festival network. Furthermore, they are not a majority the festivals studied, and should not have dramatically affected the results.

The difficulty of considerations regarding what festivals and exhibitors to include in the study is inherent in the process of SNA. SNA holds what Scott terms a ‘boundary problem’ (2012, p. 97). When mapping a network, it can be difficult to delineate where to demarcate the boundary. This is a significant concern when conducting SNA, as for a study to be reasonably comprehensive, it must aim to incorporate all possible members of a network (Scott, 2012). In selecting the accounts of the study, I have aimed to be as comprehensive and reflective of the structure of Melbourne’s film festival network as was possible.

Upon determining which accounts would be included, I manually scored the accounts for active connections between network members. Throughout this process there was semantic analysis employed to distinguish whether a tweet included just a mention of another node (thus rated as a ‘1’), or whether it was an active endorsement or dialogue (and thus rated as a ‘2’). As noted, the data collected from the accounts led to a rating of the strength of the interaction from a ‘source’ – the interactor – to the ‘sink’ – the recipient of said interaction. The number or frequency of interactive Tweets was not counted. Links were distinguished based on the most significant form of interaction made by one agent to another over the time period.

The data that arose from this research was then graphed using open-source software, Constellation. On the graphs, links are shown as an arrow from the source to the sink, with skinny arrows denoting ‘1’ strength links, thicker arrows denoting ‘2’ strength links, and no arrows denoting no interaction. Nodes that were festivals appear as a triangle, while exhibitors were represented by a circle. As Zweig notes, graphing of this kind allows the connections between nodes to be qualitatively analysed in a tangible, comprehensible fashion (2016). This qualitative analysis was one half of the resultant knowledge gained from the process. Elements such as ‘gatekeepers’ – nodes which act as a bridge between subgroups – were searched for. Different graphs were created that highlighted ‘clusters’ – subgraphs of strong relationships – to help analyse the natural groupings that occurred within the network. Presenting the information in this form allowed for a qualitative analysis of the shape

This qualitative analysis was married with quantitative measures that arose from the software’s analysis of the data. There were four significant measures applied. All the measures are forms of ‘centrality’, measures of the importance of individual nodes within the system. Firstly, ‘betweenness centrality’ – how may reciprocal connections a node has –was measured (Zhu et al., 2010). Secondly, ‘closeness centrality’ was investigated, which measures the closeness of a node to all other nodes in their system (Scott, 2012). Thirdly, ‘degree centrality’ of the nodes was measured – a measure that describes how many times other nodes interact with a certain node, thus describing how popular a node is (Zhu et al., 2010). Lastly, ‘PageRank centrality’ was analysed – a measure that, via an analysis of the centrality of connections, describes how influential a node is within the system (Pedroche et al., 2016). These measures, coupled with the qualitative analysis, allowed me to analyse the shape and structure of the network, as well as ascertain the most significant organisations within the system.

While some limitations of this method have been discussed, is perhaps prescient to mention some more are left unresolved. Most significantly, because of the temporal and spatial specificity of the data, the results of this study will not be generalisable. This is a problem contained in both SNA and any social media analysis (Black et al., 2012; Scott, 2012). Because of the specificity of the actors within the network, as well as the timeframe studied, results will only speak to the nature of the network during the time described. Additionally, focusing on the structure and relationships of a network – as SNA does – is both a strength and a weakness. It is a strength insofar as has been discussed: it offers the opportunity to discover who are the most influential agents in the industry, and how the network is structured. It is limited insofar as each individual point receives little or shallow analysis beyond their network positioning. However, the above does not take away from strengths of this method, and its capacity to create new knowledge. As discussed, there has been substantial discussion of the nature of film festivals and exhibitors themselves, but a significant gap in literature remains with regards to describing the system in which these organisations operate.

Results

| Node: | Betweenness Centrality Measure: |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | 0.29 |

| ACMI | 0.28 |

| Palace Cinemas | 0.21 |

| Cinema Nova | 0.21 |

| Node: | Closeness Centrality Measure: |

| Melbourne International Film Festival | 0.65 |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | 0.53 |

| ACMI | 0.41 |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | 0.40 |

| Node: | Degree Centrality Measure: |

| ACMI | 0.27 |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | 0.20 |

| Palace Cinemas | 0.20 |

| Cinema Nova | 0.20 |

| Node: | PageRank Centrality Measure |

| Palace Cinemas | 0.10 |

| ACMI | 0.07 |

| Melbourne International Film Festival | 0.07 |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | 0.05 |

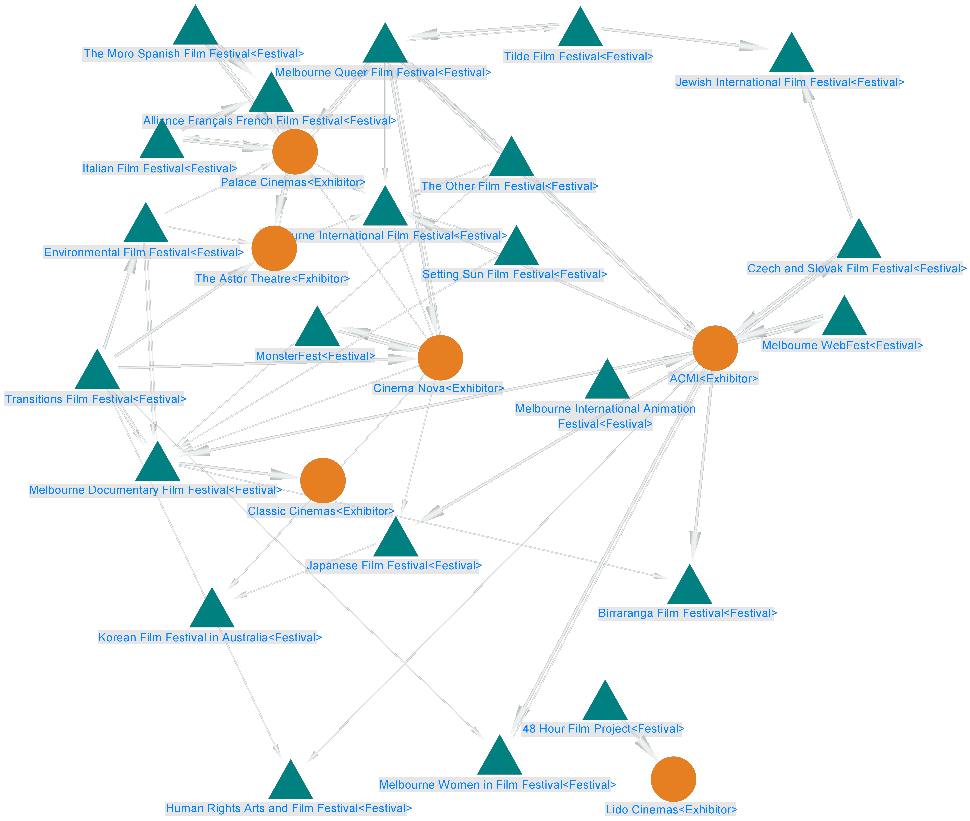

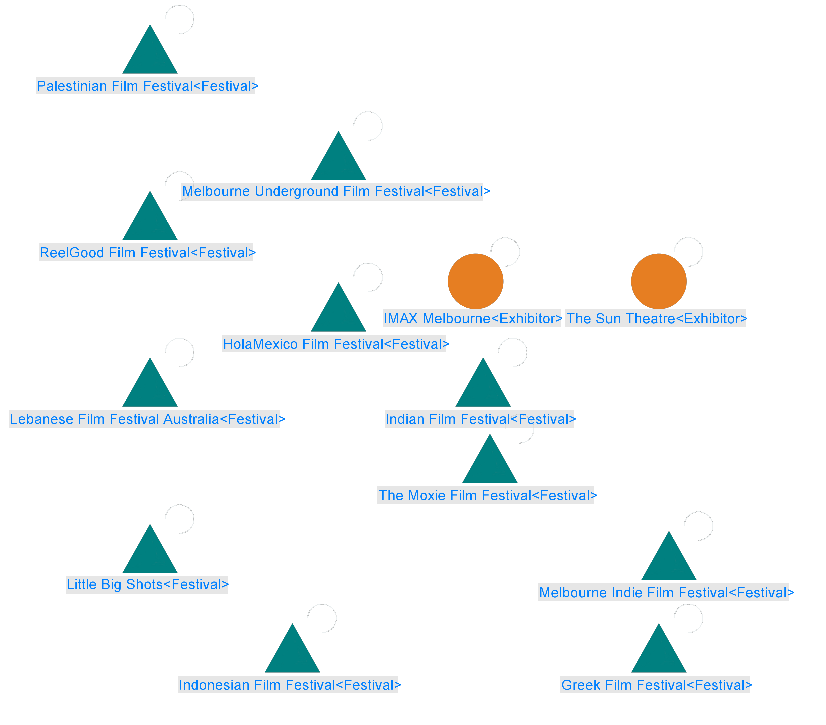

Starting with the qualitative findings: Figure 1 displays the graphed results from the research. To the left of the graph, there is a grouping of festivals that are much closer or tightly packed than the right of the graph. This is largely because many of the most influential or interconnected nodes in the graph had high levels of interaction with each other. On the right-hand side, there is a branch of nodes connected to ACMI, the most distant of the significant nodes. To the bottom-right there is a single, isolated cluster – the connection between 48 Hour Film Project and Lido Cinemas. Below the main network are the individual, non-interactive or interacted with nodes.

Figure 1 does not hold a stable shape or pattern of connections, and instead has a high variance of interactions. While there is a significant close collection of nodes to the left-hand side, many nodes – such as the Melbourne Women in Film Festival and the Human Rights Arts and Film Festival – have connections that come from each side of the graph. There is not a single navigable pathway throughout the system, but many. While the nodes have formed groups, it seems as though there are not barriers for most accounts to interact with any other account in the system. However, it is important to note that this is not the case for all nodes. Palace Cinemas acts as a gatekeeper or bridge between the interconnected network and all the Palace run festivals such as the Italian Film Festival. Thus, entry into the network for these festivals is directed through Palace Cinemas.

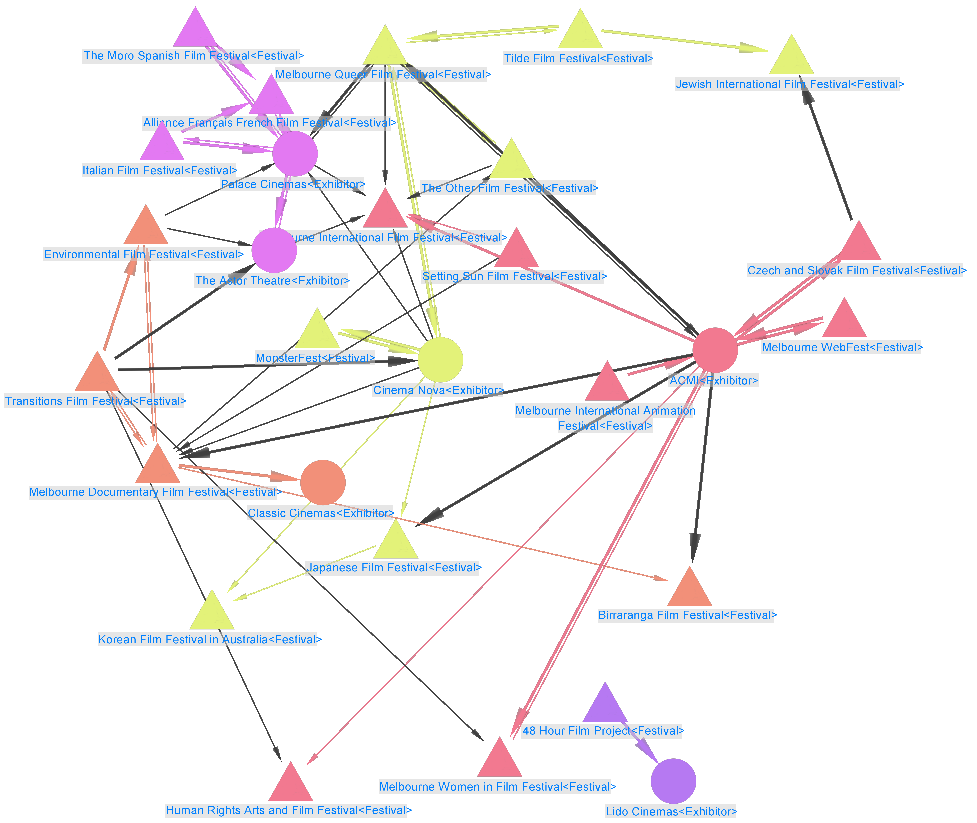

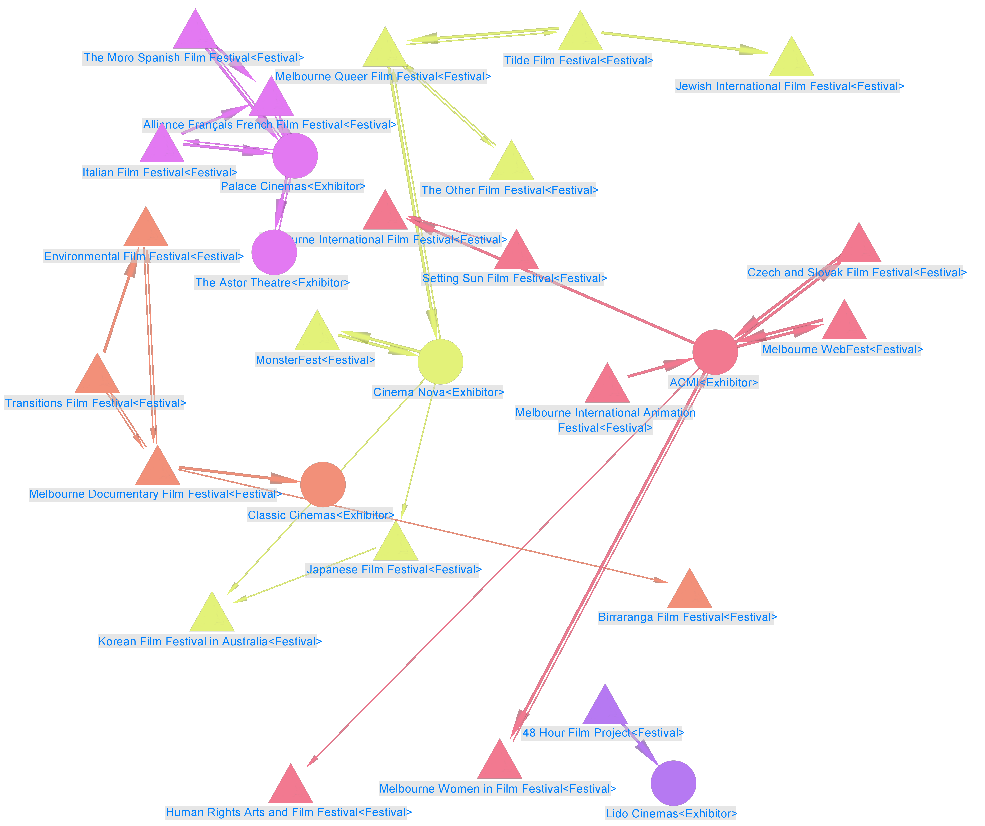

Figure 2 and Figure 3 are the same graph; however, Figure 3 gets rid of links between clusters to make it easier to read. These graphs show the natural clusters that have formed in the network. Looking to Figure 2, all the clusters are connected (besides the 2-node cluster with 48 Hour Film Project). All the clusters have central nodes which act as central points to the clusters. There is the Palace Cinema cluster (purple), the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival (MDFF) cluster (orange), the Cinema Nova/MQFF cluster (lime green), and the ACMI cluster (red). Three of the five central cluster nodes are exhibitors, and two are festivals. Most clusters are connected at some point through reciprocal interactions, besides the ACMI cluster (red) and the Palace Cinemas cluster (purple).

These clusters have also formed around trends in content or context. The Cinema Nova/MQFF cluster is largely ‘identity’ festivals. The MDFF cluster is largely concerned with ‘real world’ or advocacy content. The Palace Cinema cluster has formed around Palace owned accounts. The ACMI cluster has an industry or production context concern. These trends do not always hold true– for example, the Czech and Slovak Film Festival is in the ACMI cluster. However, in general, these clusters have content or context themes.

Turning attention to quantitative results: 25% of exhibitors held no links – being neither a source or a sink. This was more pronounced in festivals, with 33% of festivals studied acting neither as a source or a sink. Of those in the central network, 20% of exhibitors were only sinks – they themselves initiated no interaction. Again, this was slightly higher in festivals at 23%. Lastly, in the central network only one festival and one exhibitor had a single link.

Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, and Figure 7 present the top four nodes in each of the measures of centrality applied to the data. There will be a conversation with regards to what these measures mean in the coming discussion section. Of note here, six nodes of the network made an appearance in the top four of these measures. These nodes are Palace Cinemas, ACMI, Cinema Nova, MQFF, MIFF and the MDFF. As such, these are measurably the six most significant actors in the network. Interestingly, there is an even-split here between exhibitors and festivals.

Discussion

Overall, the process of applying SNA to the collected Twitter data led to both surprising and expected outcomes. This discussion section will aim to expand on the results and connect them to the research aims: to analyse the shape and structure of Melbourne’s film festival network, and to illuminate the network’s most influential actors.

In Figure 1 thereis a tight grouping to the left of the graph. As noted in the results, this is because five of the six identified key actors of the network are positioned in this section of the graph. This is particularly interesting as it suggests not only that most of the significant actors are linked – or separated by one degree – with one another in the system, but that they are also linked to similar less-significant actors in the network. The closeness of the left side of the graph suggests that there is a sub-network of sorts, consisting of a set of highly interactive organisations positioned close to the most influential actors in the system.

Furthermore, both the reality that the clusters arose with general themes, and the diversity of possible connections, speaks to Stevens’ contention that Melbourne’s festival system is not saturated enough to be competitive (2011). Firstly, it should be noted that demarcating clusters within the graph – as is done in Figure 2 and Figure 3 – is not a perfect process. Unlike the quantitative functions of Constellation, the cluster function requires user input. However, Figure 2 and Figure 3 certainly help illuminate the closeness of festivals with similar themes or organisational contexts. This eventuation seems to cohere with Stevens’ contention that the festivals are not in competition (2011). If these festivals were in direct competition, it would perhaps make them more reticent to directly connect with other festivals of a similar type – such as the Transitions Film Festival and the Environmental Film Festival which have similar subject matter. Realistically, the notions of ‘identity’ or ‘advocacy’ festival that I set up as an overarching group may be fraught, as it belies the diversity of what identities or advocacy topics; a diversity that would suggest non-competitiveness.

On the other hand, Figure 1 suggests that perhaps exhibitors are competitive. This is because the only exhibitors to be linked to one another are Palace Cinemas, The Astor Theatre, and Cinema Nova, which are all either owned by or affiliated with Palace Cinemas. While it cannot be said with certainty, perhaps if the festivals were competitive, they would act more like the exhibitors in the network. Furthermore, as noted in the results, Figure 1 holds large variance in the distance and kind of links between nodes. As evidenced by the diversity of interactions by organisations like MQFF and MDFF, this perhaps suggests that festivals have little barriers with regards to making diverse connections across the system. Overall, the research speaks to Stevens’ assertion that the festival network remains diverse, and that film festivals are most likely not arising to supersede other festivals, but to address distributional demand (2011).

However, there are certainly other possible explanations. As noted in the results, three of the four major clusters have an exhibitor at the centre of their sub-network. This could suggest that the clusters and the interactions within them has something with the programming of exhibitors. This is obviously the case with the Palace Cinemas cluster in Figure 2 and Figure 3 – as it is made up of Palace Cinemas, The Astor Theatre – which is owned by Palace – and Palace programmed and operated festivals. Yet, it could perhaps also be said to be the case with the ACMI cluster – with festivals such as the Birrarangga Film Festival and the Melbourne Women in Film Festival having screened at ACMI. This line of thought does not carry to the MDFF cluster, which is almost entirely made up of advocacy festivals. As such, this is likely not an unyielding law of the network, but a trend amongst some of the network’s clusters.

A significant portion of the active accounts did not participate in the network. There are several reasons why this could be the case. Firstly, festival operations were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. As mentioned, many the festivals were unable to operate at all during the timeframe, and thus may have been less digitally active than in a regular period. One example of this would be the Greek Film Festival. I almost elected to not include this festival. It was technically active, but it only posted on tweet during the timeframe, and that was to address that it would not be delivering a festival in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have decreased the number of links in the network overall, and likely to have increased the number of festivals that were not interactive.

With regards to the exhibitors that were not active, their unique positioning in the network may explain their distance. Both IMAX Melbourne and The Sun Theatre are both unique and niche exhibitors. IMAX Melbourne has a super-widescreen IMAX screen, and thus programs to the cinema’s strengths accordingly – in-house and large blockbuster screenings that make use of the facility. On the other hand, The Sun Theatre is a characterful, community-oriented theatre that programs to community demand. This is represented in The Sun Theatre’s Twitter account, which is extremely active, but focuses on local audience engagement rather than connective engagement within the industry. As such, these exhibitors are perhaps on the periphery as neither relies on festivals or industry connectivity for organisational sustainability.

Another outlier is the Melbourne Underground Film Festival (MUFF). This festival is very active on Twitter, but not in a way that engenders reciprocal engagement. MUFF is what could be interpreted as Melbourne’s alt-right film festival. The festival is very abrasive with its political stances, and aggressive in its messaging. It would not likely be favourable for other organisations to associate with MUFF, nor would it be consistent with MUFF’s alternative and ‘edgy’ positioning to associate with others in the network.

Shifting focus to the significant actors in the system: the results clearly indicated that there are six major actors in the film festival network. Starting with Palace Cinemas: as noted in Figure 7, Palace Cinemas had the highest PageRank centrality. This measure marks influence by considering both the number of connections, and the network influence of the nodes being connected with. This is interesting because, as noted in the literature review, Palace Cinemas operates in an idiosyncratic corner of the film festival industry. The distributor-driven festival model operated by Palace means that Palace Cinemas acts a gatekeeper or conduit between their festivals and the rest of the festival network. Their influence in the overall system is certainly compounded by this fact. And this measure of influence could have been higher in this study if all Palace festivals, such as the British Film Festival, had Twitter accounts.

An unsurprisingly significant actor in the network was ACMI. Operating as Melbourne’s moving-image museum, it would be contradictory to ACMI’s organisational mission to not be a significant factor in the film festival network (Australian Centre for Moving Image, 2019). As per Figure 6, ACMI rated highest in degree centrality – ACMI had the most connections of any node. ACMI’s industry positioning was also reflected in the nodes reach within the graph: linking with both the MDFF and MQFF on opposite ends of the graph. Perhaps what was most surprising with regards to ACMI was that in the period no direct links were made with other exhibitors.

Cinema Nova is perhaps the least significant of the significant actors. As per Figure 4 and Figure 5, Cinema Nova ranked in the top four for betweenness centrality – a measure of how connective a node is – and degree centrality – a measure of the number of connections. These measures illustrate how Cinema Nova is involved and connectively active within the system. However, it is the least impactful of the significant exhibitors in the system.

MIFF’s influence in the network was particularly interesting as it is the only significant agent that did not act as a source of any links. As recorded in Figure 5, MIFF had the highest closeness centrality – meaning it was the most (spatially) central node in the network. While it is not clear, perhaps one explanation for this is the size and real-world actions of MIFF. MIFF was one of few festivals – and certainly the largest – that went ahead with online delivery last year. The timing of that online delivery was also significant: as it occurred during Melbourne’s gruelling second COVID-19 lockdown. In this sense, there was a temporal significance to MIFF’s online delivery that could have caused a diverse selection of the industry to discuss and comment on MIFF.

Another significant festival, MQFF, differed greatly from MIFF. This was insofar as MQFF was extremely dialogically active. This is illustrated in Figure 4, as MQFF had the highest betweenness centrality. MQFF had reciprocated links with four other organisations in the network. ACMI, which rated 2nd in betweenness centrality, had the same amount. However, for MQFF, three-of-four reciprocated links were made with exhibitors. Exactly why this was the case is not in the scope of this project. Yet, it is interesting insofar as MQFF was a film festival reciprocally connecting with exhibitors over other festivals.

Lastly, MDFF was a significant illustration that within the parameters of the study, and in the network studied, quantity could lead to significance. Looking to Figure 5 and Figure 6, MDFF ranked highly in degree centrality and closeness centrality. Looking to Figure 1, this seems to have come from the quantity and diversity of MDFF’s links throughout the network. As noted earlier, there was a specific focus here on various advocacy and identity festivals: festivals which advocated for environmental change, or celebrated and affirmed a non-hegemonic identity.

Conclusion

As was discussed in the methods section, a limitation of SNA and qualitative methodologies is a lack of generalisability. Realistically, this research direction meant that it could only extend so far and discuss what is inside the scope of the project. Due to the project’s focus on ascertaining the structure and important agents of the network, measures like Tweet frequency between organisations were not included, nor was there in-depth textual analysis of the tweets themselves. Furthermore, the use of Twitter as the platform of study equated ‘significance’ within the system with social media reach. While social media reach is likely connected to organisational significance and allowed for SNA analysis in this scope, is not necessarily a direct analogue to organisational magnitude in the ‘real-world’ network.

Yet, that is not to say that this research is insignificant. Through SNA this article was able to describe Melbourne’s film festival network for the period between March 1st 2020, and March 1st 2021. This further illustrated the likelihood of festival market anti-competitiveness, yet highlighted a possible competitiveness between exhibitors. The results of this research also identifies and highlights the gravitational significance of the major organisations in the system, and their connective importance. Furthermore, while Carrol Harris and Richards (2020) have discussed Palace and distributor-driven festivals, mapping the network illuminates the separated positioning of this for-profit kind of film festival. Highlighting Palace’s network significance in this way emphasises the necessity of developing a deeper comprehension of the effect the emergence of this model has on Melbourne’s film festival system, and Australian film distribution more widely.

The nature of descriptive studies is that they can raise more questions than they answer. This was certainly evident in how often ‘perhaps’ and ‘likely’ had to be injected as qualifiers in this article’s discussion. But there is also a significant benefit to highlighting future areas of study. The methods of this study could be replicated and compared with a ‘normal’ year-long timeframe, further contextualising the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps future research could provide in-depth organisational analysis of the significant actors within the network to expand on what individual qualities make them so. As festivals – thanks to blockbusterisation – likely develop to be necessary for the in-person distribution of mid-to-low budget films, understanding how the markets and systems in which these festivals operate will become increasingly crucial; not just for film festival studies, but for ensuring the sustained production of these films.

Appendices

Exhibitor Accounts Studied:

- ACMI: https://twitter.com/ACMI?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

- Cinema Nova: https://twitter.com/cinemanova

- Classic Cinemas: https://twitter.com/Classiccinemas

- IMAX Melbourne: https://twitter.com/IMAX_Melbourne

- Lido Cinema: https://twitter.com/lidocinemas

- Palace Cinemas: https://twitter.com/palacecinemas

- The Astor Theatre: https://twitter.com/astor_theatre

- The Sun Theatre Yarraville: https://twitter.com/thesuntheatre?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eautho

Film Festival Accounts Studied:

- Alliance Francais French Film Festival: https://twitter.com/af_fff_aus

- Birrarangga Film Festival: https://twitter.com/birrarangga

- Czech and Slovak Film Festival: https://twitter.com/casffa?lang=en

- Environmental Film Festival: https://twitter.com/effa_aus?lang=en

- Greek Film Festival: https://twitter.com/greekfilmfest?lang=en

- HolaMexico Film Festival: https://twitter.com/holamexicoff

- Human Rights Arts and Film Festival: https://twitter.com/humanrightsfest

- Indian Film Festival: https://twitter.com/IFFMelb

- Indonesian Film Festival: https://twitter.com/iffaustralia

- Italian Film Festival: https://twitter.com/ItalianFF

- Japanese Film Festival: https://twitter.com/japanfilmfest

- Jewish International Film Festival: https://twitter.com/JewishIFF

- Korean Film Festival in Australia: https://twitter.com/koffiafilmfest?lang=en

- Lebanese Film Festival Australia: https://twitter.com/lffau?lang=en

- Little Big Shots: https://twitter.com/littlebigshots?lang=en

- Melbourne Documentary Film Festival: https://twitter.com/mdffest

- Melbourne Indie Film Festival: https://twitter.com/melbourneindie?lang=en

- Melbourne International Animation Festival: https://twitter.com/animationfest

- Melbourne International Film Festival: https://twitter.com/miffofficial?lang=en

- Melbourne Queer Film Festival: https://twitter.com/mqff

- Melbourne Underground Film Festival: https://twitter.com/muff_melbourne?lang=en

- Melbourne WebFest: https://twitter.com/melbwebfest?lang=en

- Melbourne Women In Film Festival: https://twitter.com/mwff_au?lang=en

- MonsterFest: https://twitter.com/monsterpics?lang=en

- Palestinian Film Festival: https://twitter.com/Palfilmfestival

- ReelGood Film Festival: https://twitter.com/ReelGoodAU

- Setting Sun Film Festival: https://twitter.com/settingsunfest?lang=en

- The 48 hour film project: https://twitter.com/48hourfilmproj?lang=en

- The Moro Spanish Film Festival: https://twitter.com/spanishfilmfest?lang=en

- The Moxie Film Festival: https://twitter.com/film_moxie

- The Other Film Festival: https://twitter.com/otherfilmfest?lang=en

- Tilde Film Festival: https://twitter.com/tildemelbourne?lang=en

- Transitions film festival: https://twitter.com/transitionsfest?lang=en#:~:text=Transitions%20Festival%20(%40TransitionsFest)%20%7C%20Twitter

Account interaction data

| Source of Interaction | Source Type | Highest Interaction Value | Recipient of Interaction | Destination Type |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 1 | Human Rights Arts and Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Birrarangga Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Melbourne Women in Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Japanese Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Melbourne WebFest | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Czech and Slovak Film Festival | Festival |

| ACMI | Exhibitor | 2 | Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 1 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 1 | Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 1 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 2 | MonsterFest | Festival |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 1 | Japanese Film Festival | Festival |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 1 | Korean Film Festival in Australia | Festival |

| Cinema Nova | Exhibitor | 1 | Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival |

| Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor | 2 | The Astor Theatre | Exhibitor |

| Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor | 2 | Alliance Français French Film Festival | Festival |

| Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor | 1 | Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival |

| Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor | 1 | The Moro Spanish Film Festival | Festival |

| Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor | 1 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor | 1 | Italian Film Festival | Festival |

| The Astor Theatre | Exhibitor | 1 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| The Astor Theatre | Exhibitor | 1 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| Alliance Français French Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival | 1 | ACMI | Exhibitor |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Cinema Nova | Exhibitor |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival | 1 | The Other Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Tilde Film Festival | Festival |

| The Moro Spanish Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| The Moro Spanish Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Alliance Français French Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne International Animation Festival | Festival | 2 | ACMI | Exhibitor |

| The Other Film Festival | Festival | 1 | ACMI | Exhibitor |

| The Other Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival |

| The Other Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| Italian Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Italian Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Alliance Français French Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Women in Film Festival | Festival | 1 | ACMI | Exhibitor |

| MonsterFest | Festival | 2 | Cinema Nova | Exhibitor |

| Japanese Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Korean Film Festival in Australia | Festival |

| Transitions Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Cinema Nova | Exhibitor |

| Transitions Film Festival | Festival | 2 | The Astor Theatre | Exhibitor |

| Transitions Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Human Rights Arts and Film Festival | Festival |

| Transitions Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne Women in Film Festival | Festival |

| Transitions Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Environmental Film Festival | Festival |

| Transitions Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival |

| 48 Hour Film Project | Festival | 2 | Lido Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Tilde Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Melbourne Queer Film Festival | Festival |

| Tilde Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Jewish International Film Festival | Festival |

| Setting Sun Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne International Film Festival | Festival |

| Setting Sun Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne WebFest | Festival | 2 | ACMI | Exhibitor |

| Czech and Slovak Film Festival | Festival | 2 | ACMI | Exhibitor |

| Czech and Slovak Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Jewish International Film Festival | Festival |

| Environmental Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Palace Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Environmental Film Festival | Festival | 1 | The Astor Theatre | Exhibitor |

| Environmental Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival | 2 | Classic Cinemas | Exhibitor |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival | 1 | The Other Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Birrarangga Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Transitions Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Documentary Film Festival | Festival | 1 | Environmental Film Festival | Festival |

| Nodes with No Interactions (Both as Source or Recipient) | Node Type |

| IMAX Melbourne | Exhibitor |

| The Sun Theatre | Exhibitor |

| Indonesian Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Underground Film Festival | Festival |

| Greek Film Festival | Festival |

| HolaMexico Film Festival | Festival |

| Palestinian Film Festival | Festival |

| ReelGood Film Festival | Festival |

| Melbourne Indie Film Festival | Festival |

| Indian Film Festival | Festival |

| Lebanese Film Festival Australia | Festival |

| The Moxie Film Festival | Festival |

| Little Big Shots | Festival |

References:

Agostino, D. (2018). Can Twitter Add to Performance Evaluation in the Area of Performing Arts? Reflections from La Scala Opera House. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 48(5), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2018.1431985

Australian Centre for the Moving Image. (2019). Annual Report 2018-2019. https://acmi.s3.amazonaws.com/media/uploads/files/Annual_Report_2018-19.pdf?Signature=V%2FJuIA4A%2FAPESmoLESDThoDDLJU%3D&Expires=1599616530&AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJJOVMAJPAFURBISA

Aveyard, K. (2009). ‘Coming to a cinema near you?’: Digitized exhibition and independent cinemas in Australia. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 3(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1386/sac.3.2.191/1

Bendle, L. J., & Patterson, I. (2008). Network Density, Centrality, and Communication in a Serious Leisure Social World. Annals of Leisure Research, 11(1–2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2008.9686783

Benson, P. (2016). The Discourse of YouTube. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646473

Black, A., Mascaro, C., Gallagher, M., & Goggins, S. P. (2012). Twitter zombie: Architecture for capturing, socially transforming and analyzing the twittersphere. Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work – GROUP ’12, 229. https://doi.org/10.1145/2389176.2389211

Carroll Harris, L. (2014). Window of Opportunity: The Future of Film Distribution in Australia. Metro Magazine, 182, 98–103. https://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=2c725be4-a8ea-46a8-b1d1-d21dc217fa0d%40pdc-v-sessmgr02

Carroll Harris, L. (2017). Theorising film festivals as distributors and investigating the post-festival distribution of Australian films. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 11(2), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2017.1356611

Constellation. (n.d.). Homepage. https://www.constellation-app.com/

Corbett, B., & Edwards, A. (2018). A case study of Twitter as a research tool. Sport in Society, 21(2), 394–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1342622

Davies, J., & Merchant, G. (2009). Web 2.0 for schools: Learning and social participation. Lang.

Festevez. (n.d.). Homepage. https://festevez.com/

Foreman-Wernet, L. (2017). Reflections on Elitism: What Arts Organizations Communicate About Themselves. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 47(4), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2017.1366380

Gibbons, L. (2007). Cultural film heritage and independent film production in Australia. Archives and Manuscripts, 35(1), 34–52. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200709074

Grandjean, M. (2016). A social network analysis of Twitter: Mapping the digital humanities community. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1), 1171458. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.11714585

Hausmann, A., & Poellmann, L. (2013). Using social media for arts marketing: Theoretical analysis and empirical insights for performing arts organizations. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 10(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-013-0094-8

Houston, J. B., Hawthorne, J., Perreault, M. F., Park, E. H., Goldstein Hode, M., Halliwell, M. R., Turner McGowen, S. E., Davis, R., Vaid, S., McElderry, J. A., & Griffith, S. A. (2015). Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters, 39(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12092

Hoyler, M., & Watson, A. (2019). Framing city networks through temporary projects: (Trans)national film production beyond ‘Global Hollywood’. Urban Studies, 56(5), 943–959. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018790735

ICA. (n.d.). Member Cinemas. http://www.independentcinemas.com.au/m/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=48&layout=blog&Itemid=83

Kent, J. (Director). (2014). The Babadook [Film]. Causeway Films.

Kim, M. (2020). Does Vertical Integration of Distributors and Theaters Ensure Movie Success? Journal of Asian Sociology, 49(1), 99–120. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/26909867

Knoke, D., & Yang, S. (2008). Social Network Analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985864

MIFF. (2021). 37o South Market. https://miffindustry.com/37osouth-market/

O’Reilly, T. (2005). What is Web 2.0. O’Reilly Media Inc. https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

Ovadia, S. (2009). Exploring the Potential of Twitter as a Research Tool. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 28(4), 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639260903280888

Pedroche, F., Romance, M., & Criado, R. (2016). A biplex approach to PageRank centrality: From classic to multiplex networks. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 26(6), 065301. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4952955

Peranson, M. (2008). First You Get the Power, Then You Get the Money: Two Models of Film Festivals. Cinéaste, 33(3), 37-38. https://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=ef5fab8e-ac37-4f5c-8f0c-0a816e9176eb%40sessionmgr103.

Preece, S., & Wiggins Johnson, J. (2011). Web Strategies and the Performing Arts: A Solution to Difficult Brands. International Journal of Arts Management, 14(1), 19–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41721114.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3A5562a0c4a6b5f669dc1987d7706cb98f

Rhyne, Ragan. (2006). The Global Economy of the Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 12(4), 617–619. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2006-005

Richards, S. (2016). Proud in the middleground: How the creative industries allow the Melbourne queer film festival to bring queer content to audiences. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 10(1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2016.1140467

Richards, S., & Carroll Harris, L. (2020). From the event to the everyday: Distributor-driven film festivals. Media International Australia, 1329878X2093847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20938479

Ricke, L. D. (2014). The impact of Youtube on U.S. politics. Lexington Books. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=1809830

Scott, J. (2012). What is Social Network Analysis? Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781849668187

Senekal, B. A. (2014). An investigation of Pierre de Wet’s role in the Afrikaans film industry using social network analysis (SNA). Literator, 35(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.4102/lit.v35i1.1099

Slatten, L. A. D., Guidry Hollier, B. N., Stevens, D. P., Austin, W., & Carson, P. P. (2016). Web-Based Accountability in the Nonprofit Sector: A Closer Look at Arts, Culture, and Humanities Organizations. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 46(5), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2016.1211048

Stevens, K. (2011). Fighting the Festival Apocalypse: Film Festivals and Futures in Film Exhibition. Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture and Policy, 139, 140–148. https://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=7843ebc3-7578-4306-bad4-0e07b51c45fe%40pdc-v-sessmgr01

Stevens, K. (2016a). Australian film festivals: Audience, place, and exhibition culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Stevens, K. (2016b). Enthusiastic amateurs: Australia’s film societies and the birth of audience-driven film festivals in post-war Melbourne. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 14(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2015.1106689

Stevens, K. (2016c). From film weeks to festivals: Australia’s film festival boom in the 1980s. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 10(2), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2016.1198450

Suzić, B., Karlíček, M., & Stříteský, V. (2016). Social Media Engagement of Berlin and Prague Museums. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 46(2), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2016.1154489

Veal, A. J., Burton, C., & Pearson. (2014). Research methods for arts and event management. Pearson.

Verhoeven, D. (2007). Twice born: Dionysos Films and the establishment of a Greek film circuit in Australia. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 1(3), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1386/sac.1.3.275_1

Verhoeven, D., Musial, K., Palmer, S., Taylor, S., Abidi, S., Zemaityte, V., & Simpson, L. (2020). Controlling for openness in the male-dominated collaborative networks of the global film industry. PLOS ONE, 15(6), e0234460. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234460

Wong, C. H.-Y. (2011). Film Festivals. Rutgers University Press; JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hjg83

Zhu, B., Watts, S., & Chen, H. (2010). Visualizing social network concepts. Decision Support Systems, 49(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2010.02.001

Zweig, K. A. (2016). Network Analysis Literacy: A Practical Approach to the Analysis of Networks (1st ed. 2016). Springer Vienna: Imprint: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-0741-6

Leave a comment