The Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) has seen amendments, such as the introduction of more ‘fair dealings’ exemptions over the past 20 years. However, the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) remains an owner-centred doctrine that neglects to consider the users of Intellectual Property (IP). As legislation stands, Australia offers little protection for harmless, creative and transformative uses of IP, such as those of the creators of fan-made merchandise. In this essay, I explore the phenomena of fan-made merchandise on the online craft-marketplace Etsy. Upon investigating a transformative fan-made product derived from the film The Babadook (Kent, 2014), I reflect on how the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) currently offers no protection for such transformative expressions of fandom. Lastly, I conclude that as the current system serves not the creators of IP or those who use IP, but large IP owning companies, legislators should reconceive of fair dealings as not just exemptions, but the rights of users.

First, it is important to note that copyright is perhaps not the first issue that comes to mind with Etsy’s operation in Australia. A quick search for items related to most any copyrighted entity on the site will turn up obvious infringement of the Trademark Act 1995 (Cth). A search on the site of items related to the film The Babadook (2014) – which will be used as an example later in this essay – turns up a lot of fan-made posters, prints, and reproductions of the film’s marketing material. One example comes from user PigeonHoleCards (n.d.), who, at the time of writing, is selling birthday cards with the film’s titular monster on. They are likely infringing under section 120, subsection 2 of the Trademark Act 1995, as they could be considered as using a “sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trademark” – if Causeway Films (the film’s producer) has trademarked the promotional image of the Babadook character for similar products.

Where the discussion of Etsy and trademark infringement perhaps gets more interesting is when companies in control of a IPs trademark certain designs or product types in response to fan demand. Santo remarks upon this phenomenon taking place within the TV Series Firefly’s(2002) fandom (2018, p. 335; see also Hall, 2013). Fans of the show produced and sold idiosyncratic knitted hats worn by one of the show’s main characters. The popularity of these bespoke hats then incited merchandise website ThinkGeek to purchase a licence from the IP holders of Firefly to produce these hats exclusively. The result was Fox – holder of the show’s IP – sending cease and desist claims to the original sellers and makers of the hats. An in-depth analysis of this scenario and how it pertains to Australian trademark legislation is not within the scope of this project. However, perhaps some of the discussion of fandom, fan-made merchandise, and the lack of user’s rights in Australian IP legislation may shed some light on why the above is problematic, and worth future study. While the trademark aspect of this topic is interesting, a limitation of this essay is that this discussion will not be actively developed further.

Fandoms, material fandom and the fan-made

Fans are those users of media and IP’s that hold the most intimate, strong, and powerful connection to the text. But more than that, as Jenkins (2006) contends, fan interactions and fandom often become intractable elements of the lifecycle of media. Fans, in many cases, do not stop at the consumption of a text, but are an essential driving force behind a text’s continued relevancy, or ‘life’ (Jenkins, 2006, p. 21). This can take the form of extending reach and temporal relevancy of a text, as well as revitalising the life of a text that had ceased to be in the public eye (Jenkins, 2006, p. 21).

However, this is not a one-way relationship where fans simply give life to a text for nothing but consumption in return. Jenkins (2000) contends that fans connect with texts through a dual state of fascination and frustration: allured and excited by the textual and ideological manifestations of the text but frustrated in how texts can never fully conform to what they desire. This dual fascination and frustration occurs naturally, but can also evolve intentionally from authors who engender fan engagement through an awareness of the progressing ‘fanon’ – the fans supratextual canon (Wolf, 2012). Jenkins (2000, p. 176) contends that from this initial engagement fans form ‘interpretive communities’ – groupings of individuals with similar ideologies, interpretations and levels of engagement with the text. And with the formation of these interpretations comes the beginnings of the friction that can occur between fandoms and the IP holders of media: as while fans can propel and encourage engagement with texts, it can be hard to control what form that engagement will take (Lessig, 2009).

An essential and undertheorised element of fandoms is how they materially engage with their chosen texts. Hills (2014) and Santo (2018) both note that there has been an academic reticence to engage directly with the material, the merchandisable, and the transactional elements of fandoms. Hills (2014) specifically contends that this gap has come from academics trying to grapple with the community and transmedial aspects, as well as how relationships can be developed in fandoms. As a result, scholars have avoided discussion of material elements of fandom in order to escape the confounding of fandom and consumerism (Santo, 2014). Furthermore, Hills (2014) contends that ‘material fandom’ – such as collecting – has largely been coded male, and thus has not been the chief concern of most fandom studies, which has its genesis in feminist scholarship.

And yet, merchandise can play an important role in the navigation of individuals through fan spaces – both private and public. Merchandise can often act as a physical manifestation or notation of a fan’s engagement with a text – where financial investment becomes a signifier of emotional investment (Santo, 2018, p. 330). In this sense, the purchasing of merchandise can operate as the cost of entry to a fandom, where merchandise can be a substantial element of ‘fan-curation’: the process by which new fans enter into an existing fan community (Geraghty, 2013; Kompare, 2018). Yet, connections to merchandise can acquire personal significance outside of the community. Hoebink et al. (2014), Sandvoss (2005) and Santo (2018) all contend that the consumption of merchandise does not stop at purchase. Instead, there is a personal and purposeful nature to the acquisition of fan items. Merchandise – through its connection to the fan’s text – comes loaded with fondness, memories, nostalgia, or sense of place (Santo 2018). As such, material fandom and fan communities often form around the stories and personal connection to artifacts, and less so to the economic reality of the items themselves (Geraghty, 2013). Sandvoss asserts that this relationship between fan and object “… removes their object of consumption from the logic of capitalist exchange” (2005, p.116). I find Sandvoss’ assertion somewhat drastic, as while there is added significance and paratext to the purchasing of merchandise by fans, they are still – for the most part – being sold such artifacts in a capitalist setting. Nevertheless, material association is an important, personal, and often connective portion of the fan experience.

As noted, the stories that surround the fan items are often of more concern than their economic value. Thus, authentic objects with a story and personal or community connection between creator and user are becoming growingly popular (Santo, 2018). This often takes the form of fan-made merchandise: what Santo describes as “authentic expressions of fannishness” which are “rooted in the crafter’s allegiance to… particular fan communities” (2018, p.333). It is important to note that ‘fan-made’ is a recent departure from ‘fan-creation’, where transactions happened on a smaller and in-person scale at conventions and gatherings (Santo, 2018). Yet, Santo argues that in this new form of transaction the importance of the connection between crafter and user still remains – whether immediate or perceived (2018).

While ‘authenticity’ online is often a fabricated attribute (Dekavalla, 2020), it is perceived authenticity and community originality that is central here. This was displayed in a study conducted by King and Ridgway (2019), in which female Star Wars fans were interviewed about their merchandise tastes. Most of the participants of the study suggested that ‘uniqueness’ was a more important determinant than price when making merchandise purchases (King & Ridgway, 2019, p.237). This came from a sense that there was a more personal connection to the object when the item was not something ‘every fan in the world has’ (King & Ridgway, 2019, p.237). Furthermore, the participants noted that – as women in a male dominated fandom – their merchandise demands were not being met by the holder of the Star Wars IP (King & Ridgway, 2019). As such, bespoke and fan-made merchandise can be a means of access into material fandoms for those not part of the IP holder’s imagined audience. And this carries back to Jenkins’ concept of fandoms being made up of ‘interpretive communities’. Fan interpretation – in this setting actualised through fan-made merchandise – is what is central to fandoms and what makes them interesting and engaging communities, not necessarily the interpretive parameters set by the IP holder.

While fan engagement, community, and connections with merchandise are not new phenomena, they have all been dramatically altered with the introduction of web 2.0 platforms. ‘Web 2.0’ is a term that was introduced by O’Reilly (2005) to describe the major shift in regular use of the internet by users in the early-2000s (Benson, 2016). Web 2.0 platforms are online sites which do not create content themselves but instead supply the means for individual users to interact and distribute content of their own (Davies and Merchant, 2009; Healy and Cunningham, 2017; Houston et al., 2015). As Morris argues, these platforms have become essential elements of fandoms; both as objects of fandom themselves, but also as the means through which modern fandom is ‘organised and commodified’ (2018, p. 356). This commodification in-part refers to the creation and sale of fan-made merchandise. It is in this sense that the growth of the fan-made can be seen as part of a larger and often unreasonably romanticised phenomenon: the rise of the self-employed digital creative (de Peuter, 2011; Lange, 2014).

When it comes to the selling of the fan-made, Etsy is the web 2.0 platform of choice for many. Fan’s obsession with the authentic has married perfectly with the craft-centric online marketplace (Santo, 2018, p.333). Yet, there has been a reticence to academically comment on the nature of the platform, especially with regards to how fandoms operate on it. This is perhaps connected to the aforementioned fear of confounding fandom and the fan-made with consumerism. However, Santo contends this fear is perhaps unfounded (2018). Speaking from personal experience, Santo (2018) notes that in many cases fans approach the vendors on Etsy with ideas to commission fan-made items. From this, traditional and involved fan interactions still take place, where both parties – vendor and user – become interpersonally intertwined in a way that transcends traditional consumerist interaction.

Transformative web 2.0 interactions of this kind – positive and interpersonal as they may be – present significant challenges to existing conceptions of copyright. In the next section, I will briefly discuss a particular transformative fan entry on the Etsy marketplace that caught my eye. From this, there will be a discussion of what protections – if any – would there currently be for such a work. This will finally lead to an appraisal of the current protections for such an item under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), followed by a discussion of how legislation can develop to better protect and incorporate the copyright user.

The ‘Babe-adook’, the Copyright Act 1968, and the user

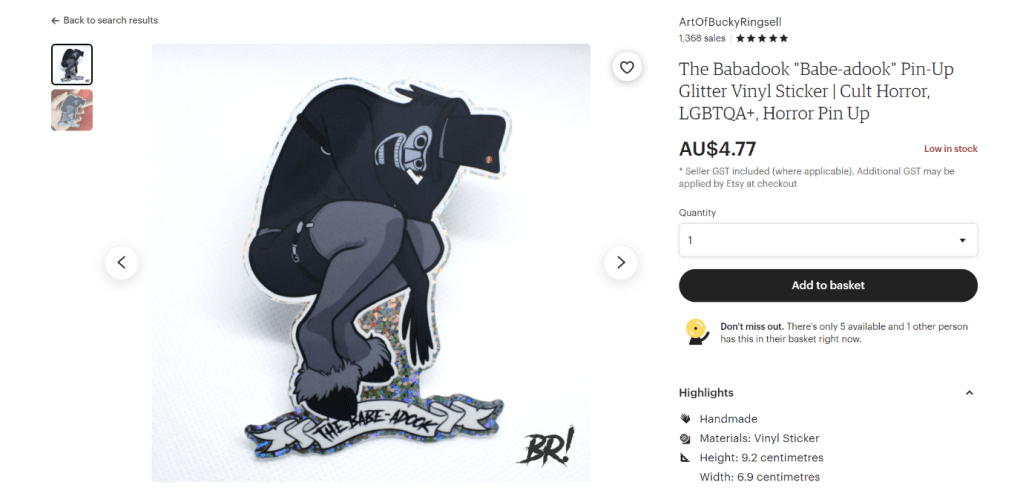

Director Jennifer Kent’s feature film debut, The Babadook, follows a single-mother and her child, as they are tormented by a dark and mysterious monster – Mister Babadook – who is a manifestation of the mother’s guilt and grief. The content of the film, as well as its success are not the chief concern here. Instead, what is interesting is the fandom that has arisen around the film. After a user of blogging website Tumblr joked that the Babadook was openly gay, the imagination of a wider queer interpretive community was sparked and brought forth a fervent and transformative online fandom (Abad-Santos, 2017; Hunt, 2017). As seen in Figure 1, at the time of writing Etsy user ArtOfBuckyRingsell (n.d.) currently has for sale a bespoke vinyl sticker of the Mister Babadook monster in a sexy ‘pin up’ style. Comically dubbed the ‘Babe-adook’, it is a product of the tongue-and-cheek queer interpretive fandom that has surrounded the film since 2016 (ArtOfBuckyRingsell, n.d.). This post is an interesting case study in transformative fan engagement, and how it is protected by Australian copyright legislation.

Firstly, it is important to ascertain that the imagery of The Babadook is protected by the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) as a ‘Cinematograph film’ under section 90. This is because the primary creators for the duration of the film were qualified persons under the act, as they are all Australian. Furthermore, the film is not itself derivative of another project, and as such, is an original work (Kwong, 2014). It would also be fair to say that the creator of the sticker has utilised a substantial part of the film in repurposing the monster; substantiality being the primary measure as to whether something is or is not an infringement (Stewart et al., 2013). Yet, while this vendor has used the imagery of the copyrighted material, their use is certainly transformative, and pulls the character and imagery into a new, creative space. Furthermore, the fan act of purchasing and adorning this sticker – which, at the time of writing amounts to an impressive 1368 sticker sales – is a celebration of the character, yet interpretively separate from the original portrayal of the character in the film. It would be amiss to say that this is an adaptation that the IP holders of The Babadook would likely creatively pursue of their own accord. Thus, while it is derivative of The Babadook, the sticker operates as a harmless manifestation of fandom, rather than project that negatively affects future renumeration of the film.

It is important to note that arguments of infringed moral rights – a creator’s right to not having their work altered in a derogatory way (Lim, 2016) – are not a common issue in this space for several reasons. First, moral rights infringements rarely make their way to court (Kallenbach & Middleton, 2015). There is only one prominent moral rights case in Australian legal history, that being Perez v Fernandez (2012). Furthermore, in the case of the above sticker, Kent has specifically noted her moral support of the interpretation (Dry, 2019). As such, moral rights will not be a significant part of the upcoming discussion.

As Australian copyright legislation stands, it seems as though the fan sticker would have little protection if the IP holders of The Babadook pursued litigation. Australia’s ‘fair dealings’ exemptions are a narrow, specific set of circumstances which allow a user to engage with copyrighted material (Kallenbach & Middleton, 2015). As noted in the Copyright Act 1968, these exemptions include; protections for research or study ((Cth) s. 40); criticism or review ((Cth) s. 41); parody or satire ((Cth) s. 41A); news reporting ((Cth) s. 42); and for increased disability access ((Cth) s. 113E). As is somewhat obvious, none of these exemptions directly address the kind of use of copyrighted material that has happened with the creation and distribution of the sticker. Perhaps the closest would be the exemption for parody and satire – as it is the only exemption that addresses a transformative use of the content.

However, ‘parody’ and ‘satire’ have not been sufficiently defined as legal terms in Australia (Condren et al., 2008). This is in part likely due to the relative newness of the parody and satire exemption – having been introduced in 2007 (Suzor, 2008). As Condren et al. (2008) uncovered, in lieu of a specific legislative definition, the Australian courts utilise the Macquarie Dictionary definition. This is a significant issue. The current definition for the terms ‘parody’ and ‘satire’ in the dictionary are substantially the same as those in the dictionary’s first edition from 1981 (Condren et al., 2008, p. 289). Furthermore, this first edition definition was derived from the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition, which has remained substantially the same since that dictionary’s first inclusion of the terms in the 1920s (Condren et al., 2008). As Condren et al. (2008, p. 274-275) argue, these definitions are legislatively dated, prioritise ‘parody’ and ‘satire’ as literary forms, and neglect to include ‘transformative’ and ‘harmless’ expressions such as the ‘Babe-adook’ sticker.

This definitional deficiency both points to and is exacerbated by a greater issue here: the current lack of consideration for the creative in copyright. Elmahjub et al. (2017, p. 274) argue that copyright has generally considered a ‘utilitarian bargain’ between the considerations of the IP holder and the IP user. However, as legislation currently stands, copyright is very ‘owner-centred’ (Elmahjub et al., 2017, p. 275). In a certain sense, this is understandable. Copyright specifically seeks to assure renumeration and rights for IP creators, with the high-cost of creation and low-cost of distribution in mind (Kwong, 2014). Yet, as was shown in Throsby and Petetskaya’s recent report of the Australia Council (2017, p. 74), the majority of Australian artists earn less than $10,000 a year from creative practice – their copyrightable work. Elmahjub et al. argue that this indicates that copyright is not leading to renumeration for artists – hence copyright being ‘owner-centred’ and not ‘creative-centred’ (2017). Flew et al. extend this idea, suggesting that current copyright legislation is ignorant to the fact that creative industries – resultant of high-production costs – are structurally oriented in such a way that artists must sign away their copyright in order to create (2013). As such, the current strength of copyright legislation does not serve the creators of IP, but large companies with the finances to own it.

Along with poor artist renumeration, copyright infringement cases for fan-made items rarely make it to court. Because large organisations own the bulk of pop-culture IP, IP owners generally have the means to bully fan-made creators who are seen to infringe upon copyright to reach a resolution outside of court (Kallenbach& Middleton, 2015; McKay, 2011). This means that there is little-to-no precedence for fan-made creatives being litigated. As such, there is little chance for judges to advance definitions or copyright – such as ‘parody’ and ‘satire’ – through common-law rulings. Ultimately, the structure of creative industries means that those who should benefit from copyright do not, and fandoms that seek to engage in harmless and transformative creative work can be bullied into submission.

If copyright does not benefit those who create the IPs in the first place, then it should at least be adapted to consider the power imbalance resultant from who really owns IP. As many have noted, a first step in this process is the recognition of user’s rights (Cohen, 2005; Elmahjub, 2017; Sun, 2011; Trusow, 1999). In the short term, this could come from the inclusion of an exemption for transformative use of copyright – similar to the fair use exemption in the U.S (Condren et al., 2008). But perhaps a shift to considering fair dealings as the rights of users instead of exemptions from infringement could bring about greater improvement. This would not be unprecedented shift. This is how fair dealings has been ruled in Canada since 2004, when a judge set the precedent that fair dealings exemptions be considered as unrestrictive rights of users (CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada, 2004). This shift is not just semantic: rights are more empowering than an infringement exception. In the case of the ‘Babe-adook’ and other fan-made crafts on Etsy, it would be empowering to know that their creative practice is not only protected, but a right; something to be encouraged, and allowed to flourish.

For the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) to reflect the needs of a post-web 2.0 world, there needs to be a shift towards considering IP use as a right. The ‘Babe-adook’ and other fan-made artifacts on Etsy can offer transformative ways for IP users to engage with texts. These artifacts often represent more than just a purchase. They can have substantial interpersonal, cultural and community value. Furthermore, they often arise out of a community’s needs for merchandise that is authentically connected to and caters for identities more diverse than IP holders often care to consider. As such, acknowledging these artifacts and their creators as part of the wider consumer system is fraught. The owner-centred conception of copyright as it stands does not protect creators – both of the texts themselves, and the transformative interpretive communities that the texts give rise to. If the intended beneficiaries of copyright – IP creators – are not being renumerated, then at the very least the creation of transformative fan-made expressions such as the ‘Babe-adook’ should be a user right.

Cases and Legislation Cited:

Perez v Fernandez (2012) 260 FLR 1

CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada (2004] 1 SCR 339. https://canlii.ca/t/1glp0

Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021C00044/Download

Trademarks Act 1995 (Cth) https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2020C00103

References:

Abad-Santos, A. (2017). How the Babadook became the LGBTQ icon we didn’t know we needed. Vox. https://www.vox.com/explainers/2017/6/9/15757964/gay-babadook-lgbtq

ArtOfBuckyRingsell. (n.d.). The Babadook ‘Babe-adook’ Pin-Up Glitter Vinyl Sticker | Cult Horror, LGBTQA+, Horror Pin Up. Etsy. https://www.etsy.com/au/listing/891680103/the-babadook-babe-adook-pin-up-glitter?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=babadook&ref=sr_gallery-1-37&organic_search_click=1

Benson, P. (2016). The Discourse of YouTube. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646473

Chow, J., & Bushman, B. (2019). Hydro-eroticism. English Language Notes, 57(1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1215/00138282-7309710

Cohen, J. (2005). The place of the user in copyright law. Fordham Law Review 74(2), 347–374. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/flr74&i=363.

Condren, C., Davis, J. M., McCausland, S., & Phiddian, R. A. (2008). Defining parody and satire: Australian copyright law and its new exception. Media and Arts Law Review 3(13), 273–292. http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/

Davies, J., & Merchant, G. (2009). Web 2.0 for schools: Learning and social participation. Lang.

Day, H. (2018). How ‘The Shape Of Water’ Subtly Became The Queer, Race-Aware, #Metoo Masterpiece Of 2018. Shortlist. https://www.shortlist.com/news/the-shape-of-water-guillermo-del-toro-metoo-race-lgbt.

de Peuter, G. (2011). Creative Economy and Labor Precarity: A Contested Convergence. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 35(4), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859911416362

Dekavalla, M. (2020). Gaining trust: The articulation of transparency by You Tube fashion and beauty content creators. Media, Culture & Society, 42(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719846613

Dry, J. (2019). ‘The Babadook’ Director Jennifer Kent Says Her Film’s Gay Icon Status Is ‘Charming. IndieWire. https://www.indiewire.com/2019/06/gay-babadook-jennifer-kent-pride-lgbt-1202153072/

Elmahjub, E., & Suzor, N. (2017). Fair Use and Fairnes in Copyright: A Distributive Justice Perspective on Users’ Rights. Monash Law Review, 43(1), 274–298. http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MonashULawRw/2017/8.pdf

Falvey, Eddie. 2019. “Sexual Participation within Fan Cultures: Considering a Sex Toy as a Mode of Reception for The Shape of Water.” The Journal of Fandom Studies 7(3): 245–59. https://doi.org/10.1386/jfs_00003_1.

Flew, T., Suzor, N., & Liu, B. (2013). Copyrights and copyfights: Copyright law and the digital economy. International Journal of Technology Policy and Law, 1(3), 297–315. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/63047/

Geraghty, L. (2013). It’s not all about the music: Online fan communities and collecting Hard Rock Cafe pins. Transformative Works and Cultures, 16. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0492

Hall, E. (2013). ‘Firefly’ Hat Triggers Corporate Crackdown. BuzzFeedNews. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ellievhall/firefly-hat-triggers-corporate-crackdown#.prRvmW1Eok.

Healy, G., & Cunningham, S. (2017). YouTube: Australia’s parallel universe of online content creation. Metro Magazine, 193, 114–121. https://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=9e622b1d-969b-4936-b265-1e6cf58f753f%40sdc-v-sessmgr01&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNzbyZzaXRlPWVkcy1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#AN=edsilc.119784130254430&db=edsilc>

Hills, M. (2014). From Dalek half balls to Daft Punk helmets: Mimetic fandom and the crafting of replicas. Transformative Works and Cultures, 16. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0531

Hoebink, D., Reijnders, S., & Waysdorf, A. (2014). Exhibiting fandom: A museological perspective. Transformative Works and Cultures, 16. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0529

Houston, J. B., Hawthorne, J., Perreault, M. F., Park, E. H., Goldstein Hode, M., Halliwell, M. R., Turner McGowen, S. E., Davis, R., Vaid, S., McElderry, J. A., & Griffith, S. A. (2015). Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters, 39(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12092

Hunt, E. (2017). The Babadook: How the horror movie monster became a gay icon. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/jun/11/the-babadook-how-horror-movie-monster-became-a-gay-icon

Jenkins, H. (2000). Reception Theory and Audience Research. In C. Gledhill & L. Williams (Eds.), Reinventing film studies. Arnold: London.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9780814743683

Jones, B. (2013). Fifty shades of exploitation: Fan labor and Fifty Shades of Grey. Transformative Works and Cultures, 15. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0501

Kallenbach, P., & Middleton, A. (2015). 50 shades of infringement: Fan fiction, culture and copyright. IPLB, 29(9–10), 238–245. https://advance.lexis.com/document/?pdmfid=1201008&crid=28c34a92-9cd3-4660-819e-fd8b8782f1e9&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fanalytical-materials-au%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A5HDD-6HV1-F2MB-S2VM-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=334601&pdteaserkey=sr0&pdicsfeatureid=1517127&pditab=allpods&ecomp=1xtrk&earg=sr0&prid=bfc06ea0-070b-4aba-9a21-a9a04750eea5/

Kent, J. (Dir.). (2014). The Babadook [Film]. Causeway Films: Umbrella Entertainment.

King, M. C., & Ridgway, J. L. (2019). The female fan goes shopping: Satisfaction, involvement and utilitarian value when shopping for women’s Star Wars merchandise. The Journal of Fandom Studies, 7(3), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1386/jfs_00002_1

Kompare, D. (2018). Fan Curators and the Gateways into Fandom. In S. Scott & M. A. Click (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media fandom. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637518

Kwong, J. (2014). Fixation and Originality in Copyright Law and the Challenges Posed by Postmodern Art. Media & Arts Law Review, 19(1), 30–48. https://advance.lexis.com/document/?pdmfid=1201008&crid=5fd2e495-3ede-456a-9180-5b3684d483b4&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fanalytical-materials-au%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A5BW8-GCC1-F873-B00D-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=297867&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=2bcsk&earg=sr0&prid=c53be2c1-f18e-43a8-8843-09aa434616f1

Lange, P. G. (2016). Kids on YouTube technical identities and digital literacies. Left Coast Press. http://0-www.tandfebooks.com.cataleg.uoc.edu/action/showBook?doi=10.4324/9781315425733

Lessig, L. (2009). Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=591059

Lim, E. C. (2016). Of pride and prejudice: Mangled art, mutilated statues, hypersensitive authors and the moral right of integrity. Media & Arts Law Review, 21(2), 149–182. H https://advance.lexis.com/document/?pdmfid=1201008&crid=009bfe0b-bccd-4c49-9c4b-687f4533b285&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fanalytical-materials-au%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A5M8G-YS91-JFSV-G4T9-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=297867&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=2bcsk&earg=sr0&prid=f6845a1d-c55b-4ff4-a446-779632a36476

McKay, P. (2011). Culture of the future: Adapting copyright law to accommodate fan-made derivative works in the twenty-first century. Regent University Law Review, 24(1), 117-146. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1728150

Monteith, S. (2018). Queer As Fish. Medium. https://medium.com/@s.monteith1066/queer-as-fish-love-and-monstrous-bodies-in-guillermo-del-toros-the-shape-of-water-a60df1982928.

Morris, J. W. (2018). Platform Fandom. In S. Scott & M. A. Click (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media fandom. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637518

O’Reilly, T. (2005). What is Web 2.0. O’Reilly Media Inc. https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

Pierre N. Leval. (1990). Toward a Fair Use Standard. Harvard Law Review 103(5), 1105–1136. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341457

PigeonHoleCards. (n.d.). Babadook | Happy BaBa-Birthday! | Happy Birthday | Greetings Card. Etsy. https://www.etsy.com/au/listing/886329271/babadook-happy-baba-birthday-happy?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=babadook&ref=sr_gallery-1-9&organic_search_click=1

Ricke, L. D. (2014). The impact of Youtube on U.S. politics. Lexington Books. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=1809830

Rodriguez, M. (2018). ‘The Shape Of Water’ Is A Great Queer Best Picture Successor To ‘Moonlight’. Into. https://www.intomore.com/culture/The-Shape-of-Water-Is-a-Great-Queer-Best-Picture-Successor-to-Moonlight.

Sandvoss, C. (2005). Fans: The mirror of consumption. Polity Press.

Santo, A. (2018). Fans and Merchandise. In S. Scott & M. A. Click (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media fandom. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637518

Stewart, A., Griffith, P. B. C., Bannister, J., & Liberman, A. (2013). Intellectual property in Australia (Fifth edition). LexisNexis Butterworths.

Sun, H. (2011). Fair Use as a Collective User Right. North Carolina Law Review, 90(125), 127–200. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1985375

Suzor, N. (2008). Where the Bloody Hell Does Parody Fit in Australian Copyright Law? Media & Arts Law Review, 13(2), 218–248. https://advance.lexis.com/document/?pdmfid=1201008&crid=9b14c634-66a7-415b-858e-7e59233a0ce1&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fanalytical-materials-au%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A59SC-1YC1-F1WF-M285-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=297867&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=2bcsk&earg=sr0&prid=8404acfe-5f20-4a21-a7fe-de8fad60c08a

Throsby, D., & Petetskaya, K. (2017). Making Art Work: An economic study of professional artists in Australia. Australia Council. https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/workspace/uploads/files/making-art-work-throsby-report-5a05106d0bb69.pdf

Trosow, S. E. (1999). Economic Analysis and Copyright Law: Are New Models Needed in the Digital Age? Legal Reference Services Quarterly, 17(1–2), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1300/J113v17n01_10

van Dijck, J. (2009). Users like you? Theorizing agency in user-generated content. Media, Culture & Society, 31(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443708098245

Wheadon, J. (Creator). (2002). Firefly [TV Series]. Fox.

Wolf, M. J. P. (2012). Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=1211703

Wong, M. W. S. (2009). “Transformative” User-Generated Content in Copyright Law: Infringing Derivative Works or Fair Use? Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law 11(4), 1075–1139. https://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=4d16ad16-7b4a-4d9d-a762-ae1c91c0f1ed%40sdc-v-sessmgr01

Leave a comment