With perhaps one of the most misleading titles in western film canon, the Safdie Brother’s Good Time is anything but… For the characters that is. For me, watching it for the first time in 2022, it was a very good time. Now that the obligatory joke about the title is out of the way:

Taking place largely over the course of one terrible, terrible night, the film follows Connie (played by Robert Pattinson) as he attempts by any reprehensible means necessary to gather enough money to afford his brother’s release from prison after a bank robbery gone wrong.

While it positions itself as a pulpy, carnival-ride genre film, the Safdie’s directorial flair and scriptwriting choices leave a lot to be discussed.

Foremost to my mind is the questions raised by character of Nick – Connie’s brother – who has an undisclosed learning disability. While it is not Nick’s film per say – the events of the film most certainly driven by Connie’s misguided, uncaring tenaciousness – Good Time is interestingly bookended by scenes with Nick that highlight the tragedy of the character: that he has crystalline wants, needs, and desires that are altogether ignored by the two main parties controlling his life.

Nick is forcefully entered into government programs that allow him little to no room to communicate his wants and needs. The health workers treat him like he can’t make decisions – the ‘safety’ of the program strips him of his agency.

On the other hand, Connie’s misguided attempt to caretake for Nick inadvertently has the same effect. Connie is perceptive enough to understand that the program is negatively affecting Nick. Yet, by including Nick in an ill-considered bank robbery, Connie himself strips Nick of his agency in implicating him in a crime that results in his apprehension by the police, and prison time.

I think this an interesting, and altogether underdeveloped story in film canon: how the agency of the neurodiverse can be eroded under the misguided muse of ‘care’. Both parties, in their own ways, believe they are making the right decision on Nick’s behalf. But it is just that – they are decisions made on his behalf, not with his consent.

And yet, there is an interesting problematic angle to Nick’s portrayal. Nick is played by Benny Safdie, one of the directors and himself not (to public knowledge) neurodiverse. The Safdie brothers have in interviews stated that they had originally planned to cast an actor who was representative of the learning disability portrayed. They instead inserted Benny Safdie into the role when they realised how unrelenting the shooting schedule would be. Shooting on busy New York streets filled with public (not just extras), and requiring tight blocking and action movie sequences, they noted that they did not want the agency-stripping abuse that is depicted on camera to be re-produced behind the camera.

In a certain sense, this consideration is understandable – especially considering the film was shot on a budget of a shoestring and a ham-sandwich. Yet, it is still characteristic of western film industries that are ill-equipped and/or unwilling to be representative not only in front of the camera, but behind it too; of an industry that is all too happy to capitalize on minor instances of weaponised representation for clout or aesthetic purpose, but is altogether unwilling to support its own evolution into an industry that is inclusive of currently underrepresented groups (i.e. everyone who is not a white, middle-aged man).

I am not necessarily saying this is the whole truth for Good Time and the Safdies, nor am I saying that this invalidates the film as a captivating aesthetic product. This is a significantly larger topic of conversation that I will likely engage with again in the future after much more research and thought.

For the meantime, I would like to discuss one more thing of note about the film: the exemplary, emotive, and idiosyncratic lighting. Much has been said about the neo-noir lighting that bathes the majority of the night-time setting of the film in a gritty, grimy mask. The lighting is brilliant, and casts the twisted emotional states of the characters accross the film’s environments.

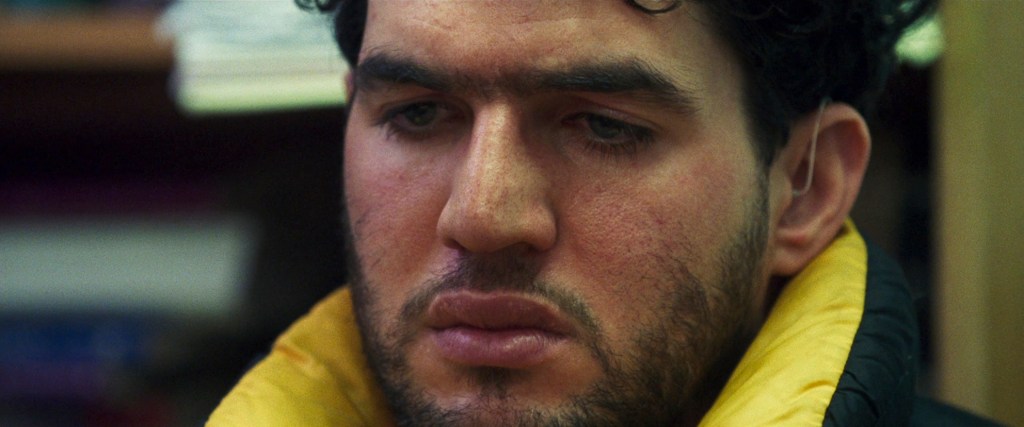

However, to my mind perhaps the most interesting element of the lighting is how it contributes to the frenetic pace of the film. This pace is established through several other significant elements. The Safdies favour longer takes, with very selective and sparse cuts that fixate the frame on the movement of the characters. This is coupled with the perpetual motion of Connie’s blocking – as the time pressure of built into the film’s narrative propels him uncomfortably and quickly through various city spaces in a state of unresting paranoia. The film is also largely composed of claustrophobic close-up shots that place the viewer uncomfortably close to the characters of the film, which promotes the audience to share their distress and need to always be on the move.

I think the lighting plays a significant and very interesting role in establishing this unrelenting pace as well. As soon as Connie commences his journey to try and ‘rescue’ Nick, the film transitions from day to night: from natural lighting to what I’m going to call hyper-real lighting.

By ‘hyper-real’ I am referring to how lighting of the film is established to be coming from light sources in the environments – but dialed up to the extreme. The film is bathed in the neon and unnatural, sparse lighting of man-made environments. Rooms are constantly saturated in pink and red lights from neon signs, or the sickly blue green of a TV showing static, or the harsh halogen lighting of a hospital. These are not some of the light sources that make up the night-time scenes of the film, they are the only light sources. In one scene a character apologises to Connie that a room has a broken light, and so can only be lit by a TV showing static in the corner. These are not metaphorical coloured lights that exist for the viewer’s aesthetic pleasure. In the diegesis of the film, night-time is coloured and lit only by these unnatural and distinctive light sources.

This shift from natural to hyper-real lighting establishes Connie’s descent into an unrelenting, and ultimately inconsequential journey: his descent into his hyper-real rabbit hole. With its fantastically extreme nature, the lighting mirrors the intensity, violence and absurdity of the film’s characters.

Connie’s unresting fugue state that lasts the majority of the film is, and was always going to be, meaningless. There is no reality where Connie’s efforts result in a positive outcome. Yet, he enters a period of fantasy where there is the palpable belief that if he just keeps moving, perhaps there could be a positive ending. Of course, that does not happen. The sun comes up, and with the natural light the unnatural belief that this could result in any way but dismally dissipates. In this way, the lighting contributes to the environment that allows Connie’s delusions to life. It is those delusions that push this fever dream of a film forward and establishes its frenetic pace.

The fantastical lighting of the film’s nightscape has a distinct temporal quality. It contributes to the pace of the film by establishing an unnatural, hyper-real, grimy atmosphere where Connie’s manipulation, violence, and perpetual motion can intelligibly aim towards and fantasy that can – come the light of day – never realistically be attained.

Leave a comment