After winning the Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture with Parasite (2019), Bong Joon-ho finally got the western recognition that he deserves. But it should be known that he has been releasing bangers his whole career.

His films are challenging and compositionally interesting. Most importantly, however, they are endlessly watchable. The most significant thing about Bong Joon-Ho in his films is that corners are never cut, and every decision is in service of the plot. His films are never burdened by strong compositional choices that are made purely for their own sake. He makes the brave choices because they are the best way to bring to life the plot, the setting, and the characters.

This is certainly true for his 2009 film, Mother. The film follows the titular Mother (played by Kim Hye-ja) on a journey to prove her son’s innocence in a local murder case. The film is a compelling, challenging, and constantly surprising murder mystery.

Side note: I apologise for this one in advance. There is a fair amount of technical jargon, and it is about a topic that some people may not be interested in: nerding out about specific editing and camera movement choices. But I wanted to write about this… So there! No complaints. You’ll take what you are given.

One element I find particularly fascinating is the fantastic camera work. There are many decisions made with regards to framing that bring to life the film’s setting and intended mood modest yet fantastically effective ways.

I have seen other discussions of this topic, particularly with regards to the aspect ratio of the film. The film was shot with a telephoto lens and has an aspect ratio of 2.39:1. In less obtuse language, film has a wide but short frame. This is significant because this aspect ratio is generally utilised for films with big landscapes or actions scenes – think Westerns of War films.

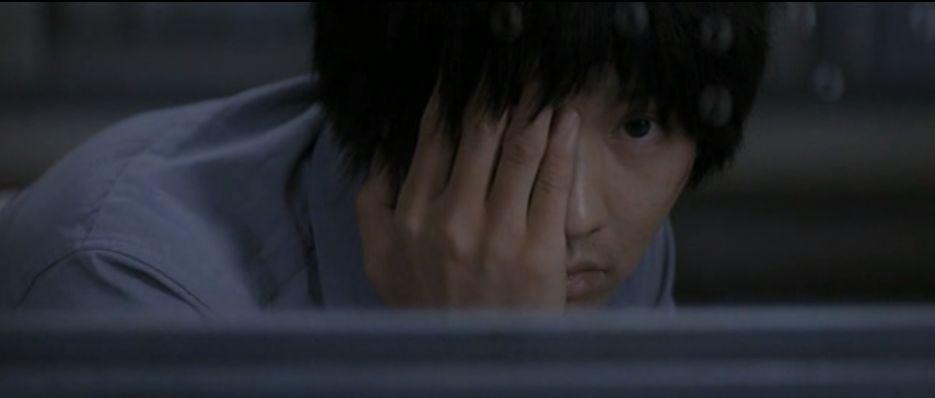

Yet, Mother takes place within city spaces – cramped streets, busses, offices, apartments. The effect of this is that close-ups are unable to capture the entirety of a character’s face, obscuring much of what would usually be shown in a more regular aspect ratio. Where the audience would usually be privy to a character’s full expression in close-ups, the tops and bottoms of character’s heads are cut off by the frame. This serves the uneasy setting of the film and the unstable mindset of the character of Mother. Details that could be important to the mystery, such as a character’s reactions to a line of questioning, are intentionally obfuscated. The aspect ratio places the audience in a similar position to the character of Mother: trying to piece together the mystery with limited information and obscured facts.

An element of the film that I have not seen discussed is how Bong and cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo utilise coordinated blocking and camera pans instead of cuts. This is most evident in how Hong and Bong capture dialogue, and how communicate the importance of elements of the environment.

Bong and Hong stray from typical filmmaking by minimising cuts in dialogue scenes. A conventional decision when two characters are engaging in an extended scene of dialogue is to shoot it with a shot-reverse-shot sequence. This is essentially cutting between a shot of one character in the discussion, and then to the other, cutting back and forth to depict their dialogue, and their reactions. It is important to note that this is convention because it is very effective. It allows the audience to grasp both sides of the discussion, focussing on each character within the dialogue in detail.

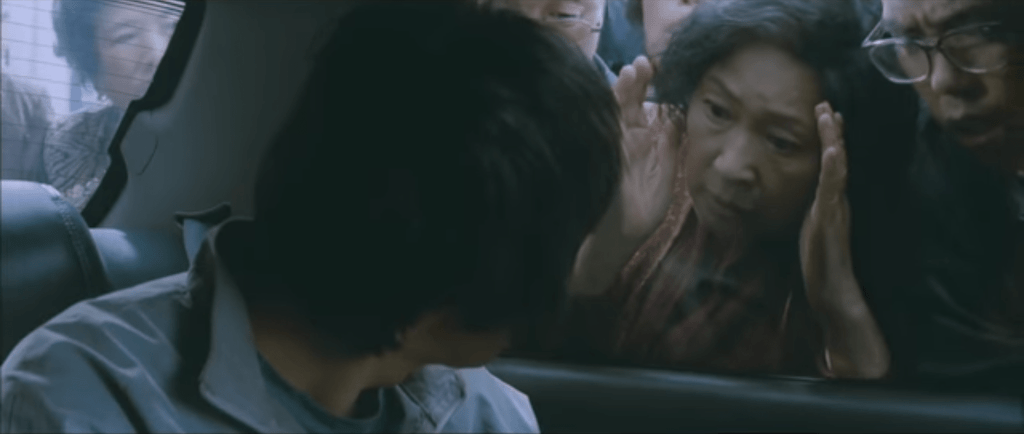

Bong and Hong do use shot-reverse-shot sequences in Mother, but they do so sparingly. Particularly in the first half of the film, Bong and Hong often elect to include both characters in the frame instead of cutting between them. One aspect of this technique is that unlike with shot-reverse-shot sequences with close-ups, the character’s faces – and thus details readable on faces such as intentions, emotions, reactions – are obscured by their distance from the frame. Similar to the aspect ratio, this helps establish the uneasy, distrusting nature of the character of mother. Another effect of this style of shooting is that the characters can be blocked closer to each other, allowing them to physically interact in ways that shot-reverse-shot sequences do not allow. Furthermore, as you do not have to cut to capture the characters in conversation, the scenes are open for actors to extend their range and is altogether a very natural means with which to view a conversation. In my daily life, at least, when I view two people talking at a table, it is unlikely that I would close my eyes before snapping my attention to the person speaking each time the conversation shifts. Instead, I would naturally switch focus from one character to the next as my eyes see fit. That just might be me. I might be the weird one.

Really though, this choice is significant because when shot-reverse-shot sequences do occur, they have an added gravity due their relative scarcity. An interesting element of shot-reverse-shot sequences is that by the mere nature of pivoting from one character to another, they imply distance between those in the conversation (literally the distance that is implied by the camera being between the characters). This distance is used in the film to heighten dialogue where characters may be oppositional or adversarial – moments where there is not only physical distance, but ideological distance. So, when we have largely been conditioned to expect dialogue to partake in two-shots (with both characters in a single take), it is more impactful when shot-reverse-shots are employed. This helps establish the stakes of the story, and the growingly adversarial nature of Mother as the film develops and the tension rises.

As mentioned previously, a substantial benefit of shot-reverse-shot sequences is that they give the audience the ability to individually parse through the respective reactions of the characters in the dialogue. This is particularly important for a story like Mother, a murder mystery where the evidence for the crime is largely constituted of what information characters are able or willing to divulge. As the film only starts employing shot-reverse-shot sequences with close-up shots more frequently in the later third, it drives up the intensity of each of these moments. It creates a fever pitch, where these interactions are given so much more gravity within the plot. Not only does it give the audience more different kinds of shots to engage with over the course of the film, but there is also addition by subtraction. Withholding such shots at the beginning of the film means that when they are employed, they have added significance and effect. Coupled with the short and wide aspect ratio, this choice helps establish the uneasy, unsettling, and thrilling nature of the mystery narrative.

Another interesting technique is Bong and Hong’s use of camera pans instead of edits. Again, conventional filmmaking practice is when you want to draw attention to some specific item/thing in a scene the film portray a character intently at the thing in question (currently out of frame). From this shot, the film will cut to a close-up of the element that the filmmakers want to make obvious, adopting the perspective of the character who was staring at the thing in question. There is nothing wrong with this technique. It is clear for a viewer and is a fantastic way to establish that something is of narrative significance, and will be consequential to the going forward. In a murder mystery like Mother, this could be something like evidence for the crime.

Bong and Hong, on the other hand, generally take a different approach. At multiple points in the film, instead of cutting to a close-up of the thing in question, Bong and Hong simply pan towards it. Often, after this pan the character investigating the thing will re-enter the frame and interact with it, and perhaps then there will be a perspective close-up for the audience to comprehend the nature of the thing further. This may sound simple (and I mean it kind of is) but I think it is brilliant, and so very refreshing.

While understanding cuts are part of film language and, having all grown up with film in our lives, a naturalised language for us all, they are not a very good analogue for how we experience the world. We do not close our eyes and completely change focus as we move through spaces – we do so with continuity. We cast our eyes over spaces as we move through them, focussing on one item to the next. Bong and Hong’s decision to use pans where cuts would conventionally exist gets to the heart of this experience. By panning through the environment to get from one point of interest to another, the viewer is given the time and means to grasp the environment with greater depth. It establishes a sense of space, not just for the characters, but for the point-of-view of the camera and the spectator. It does not just establish the existence of an important narrative element, but situates that element in the environment in which it exists.

So why are these two techniques not more conventional or widely utilised to the same effect? Well, there are many potential reasons.

It is time consuming because longer takes require much more planning. There are more things that can go wrong, and as such, it is necessary to have a greater understanding of exactly what is being shot, and exactly how it will be shot. Thus, it is necessary to take more time in the developmental planning period to make sure that everything is adequately prepared.

It is expensive because there are more chances for things to go wrong. It is potentially necessary to film more takes to have the correct amount of coverage. Less can be done to fix problems in the editing room (much cheaper as at that point you are not employing a whole crew). There may have to be more days of principle shooting (expensive thanks to the catering bill).

Lastly, it is risky because if smaller takes are being used, the editor can cobble together a scene from many different takes to make the best possible scene. On the other hand, if takes are longer and less cuts are being used, the editor is much more reliant on what was captured on set being usable. As such, it is possible that if filmmakers enter editing without correct coverage, alterations that could save scenes from having to be cut may not be feasible.

That is what make Bong Joon-ho’s filmmaking so refreshing, and so inspired. He never makes obtuse shot choices. And yet, he doesn’t cut corners and just make the simplest choice. Bong and Hong in Mother make the right camera choice for the film, regardless of the associated risks or required expertise.

I adore this film and you should too. If you haven’t seen it, give it a watch.

Please and thank you xoxoxo.

Leave a comment